If Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 masterpiece There Will Be Blood is a movie about the relentless and often cruel pursuit of progress and (more importantly) profit that drives the collective psyche of the United States of America – with Daniel Day-Lewis’s Daniel Plainview as the personification of US greed and pitilessness – then Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist is about the view from the immigrant experience in those conditions.

Viewing entries in

Drama

I wish I was more in love with director RaMell Ross’s striking and avant-garde stylistic vision for Nickel Boys. The director previously received an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature for his similarly unconventional aesthetic in Hale County This Morning, This Evening, which focuses on the Black community in Hale County, Alabama. (While researching for this review, I discovered that Ross’s inspiration for that earlier film was Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi cycle of films. I had already heard excellent things about Hale County, but, as the Qatsi trilogy is one of my cinematic touchstones, I’m now more determined to catch up with Ross’s 2018 film.)

I’ve definitely become more cynical in the decade since I started writing regular movie reviews. I’m sure of it after my reaction to seeing Jason Reitman’s new paean to the comedy institution known as Saturday Night Live. Reitman’s film, Saturday Night, is enjoyable enough as a peek behind the curtain at the madcap goings-on in the lead up to the first episode of what would become the longest running sketch comedy show in television history. It’s also cliché-ridden, offers practically zero insight into any of the characters, and features a made-to-order climax wherein everything magically falls into place at exactly the right moment. An exercise in subtlety, it is not.

Legendary filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola spent forty years trying to get Megalopolis, his sprawling, sci-fi epic fable about the Roman and American empires, made. Now 85, it might turn out to be the director’s last film. He waited about a decade too long for his examination of how and why empires crumble to be relevant. Maybe if he had made and released Megalopolis before Donald Trump’s infamous ride down that golden escalator, I would have praised his maximalist primal scream about our current cultural and political moment as visionary and prescient. Instead, what Megalopolis has on offer feels like a thin imitation of our nightmarish reality.

The Bikeriders is, on the whole, enchanted by its subjects’ nihilism. Nichols’s deep curiosity about human behavior and his non-judgmental, empathetic artistic style makes his film about small-scale fascism an engrossing portrait of our endless capacity for love and hate.

The key sequence in the procedural courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall is indicative of director Justine Triet’s masterful storytelling for what it doesn’t show us. The man who suffers the fatal titular fall, Samuel, made a surreptitious audio recording of a vicious argument between he and his wife, Sandra, that ultimately turns physically violent.

As the jury hears this altercation, Triet allows us to see what they can’t. She stages the heated exchange as a flashback, but only the portion where words are used as weapons. Before the first slap is doled out, Triet cuts back to the courtroom. We experience the physical violence between Samuel and Sandra as the jury does, who can only hear the wordless scuffle with no way of knowing who is doing what to whom.

Director Alexander Payne’s emotionally rich, quietly moving triumph The Holdovers is a study in the old cliché “before judging someone, walk a mile in their shoes.” Payne harnesses the empathetic powers of the movies – an artform the late, great Roger Ebert once called “an empathy machine” – to deliver a complex and heartfelt character study of three souls each struggling with their own demons and who find a brief solace in each other from the myriad cruelties of the outside world.

We’re not even a month into 2024, and I already have a contender for most bonkers movie of the year. Coming from Norway, The Bitcoin Car is a tragicomic musical about a small village that begins to experience troubling phenomena when a brand-new bitcoin mining facility starts operations. This movie has it all: an irrepressibly upbeat song about how death unites us all, singing electrons, an anti-capitalist worldview, and a goat named Chlamydia.

Never underestimate the power of saying something old in a fresh, new way. With his feature film debut American Fiction, writer and director Cord Jefferson is standing on the shoulders of giants – namely Robert Townsend and Spike Lee’s – with his biting satire about what kinds of Black stories interest white audiences. And while the satire might be razor sharp, Jefferson simultaneously offers up a slice-of-life story about a man coming to terms with his imperfect family, how they’ve shaped him into an imperfect person, and how he’s helped with that project himself.

How many masterpieces can one person produce? We may never know, but iconic filmmaker – and elder statesman of cinema – Martin Scorsese seems determined to find out before he’s finished behind the camera. After the likes of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, Goodfellas, and at least five other pictures that deserve consideration as masterpieces, Scorsese has done it again.

Killers of the Flower Moon is a sprawling, ambitious, deeply moving mashup of the director’s beloved gangster genre and his first Western, which wrestles with American sins that a not-insignificant portion of our population would like to bury and ignore forever.

The first time I saw Asteroid City, it was a disaster. I couldn’t connect with a single character. Each one felt like a collection of quirks hiding the fact that there was nothing below the surface. The story-within-a-story-within-a-story structure was too clever by half. After that first screening, I was ready to write off Wes Anderson’s latest effort as demonstrating a peak example of the idiosyncratic director’s style, but with none of those touching, emotionally charged moments from his previous works.

On the morning I was supposed to hammer my thoughts about the movie into a proper review, I decided to be lazy. A poor night of sleep and the siren song of the comfortable bed in the quiet early morning hours convinced me to bank more shuteye. It was the best decision I could have possibly made.

If you’re looking for the most self-assured, quietly transfixing debut feature of the year, look no further than director Celine Song’s contemplative Past Lives. I’m too old to describe her film as being “a vibe,” but that’s exactly what it is. Past Lives is like a series of emotions washing over the audience in waves. Song has taken autobiographical bits and pieces of herself to make an authentic, modern romance that feels hyper-specific to the immigrant experience and yet also universal to the human experience

It all started with an innocent enough question from my wife. She had no way of knowing when she asked it that the answer would lead to the both of us falling down a rabbit hole of cinema. (She’s been with her movie-obsessed partner long enough, though, to know that’s always a possibility. She knew who she was marrying!)

The two of us are always on the lookout for new shows we think the other would enjoy and that we can watch and discuss as we work our way through it together. Last fall, she mentioned a title she had been seeing on HBO Max for a few months – soulless media conglomerate Warner Bros. Discovery, which now owns HBO, recently rebranded the streaming service to the obnoxiously titled Max.

“Do you know anything about this Irma Vep?”

The most unlikely man to coach an English football club – in deference to the Brits, who formalized play of the sport in the late 19th century, I’ll eschew the term soccer, although there is compelling evidence that it was our friends across the pond who invented the now-hated term in the first place – is seeing himself out. He’s doing so alongside characters from several other shows touted as the best of their crop of prestige television. In the last month, HBO powerhouse series Succession and Barry both took a final bow. Now, it’s time to say so long and farewell to the irrepressibly upbeat Ted Lasso.

The transformation of the show itself over the course of its three-season run irked some early supporters. What started as a lighthearted half-hour sitcom about a fish-out-of-water American football collage coach being hired to lead a team in a sport he knows nothing about blossomed into a heartfelt dramedy about human beings connecting with one another.

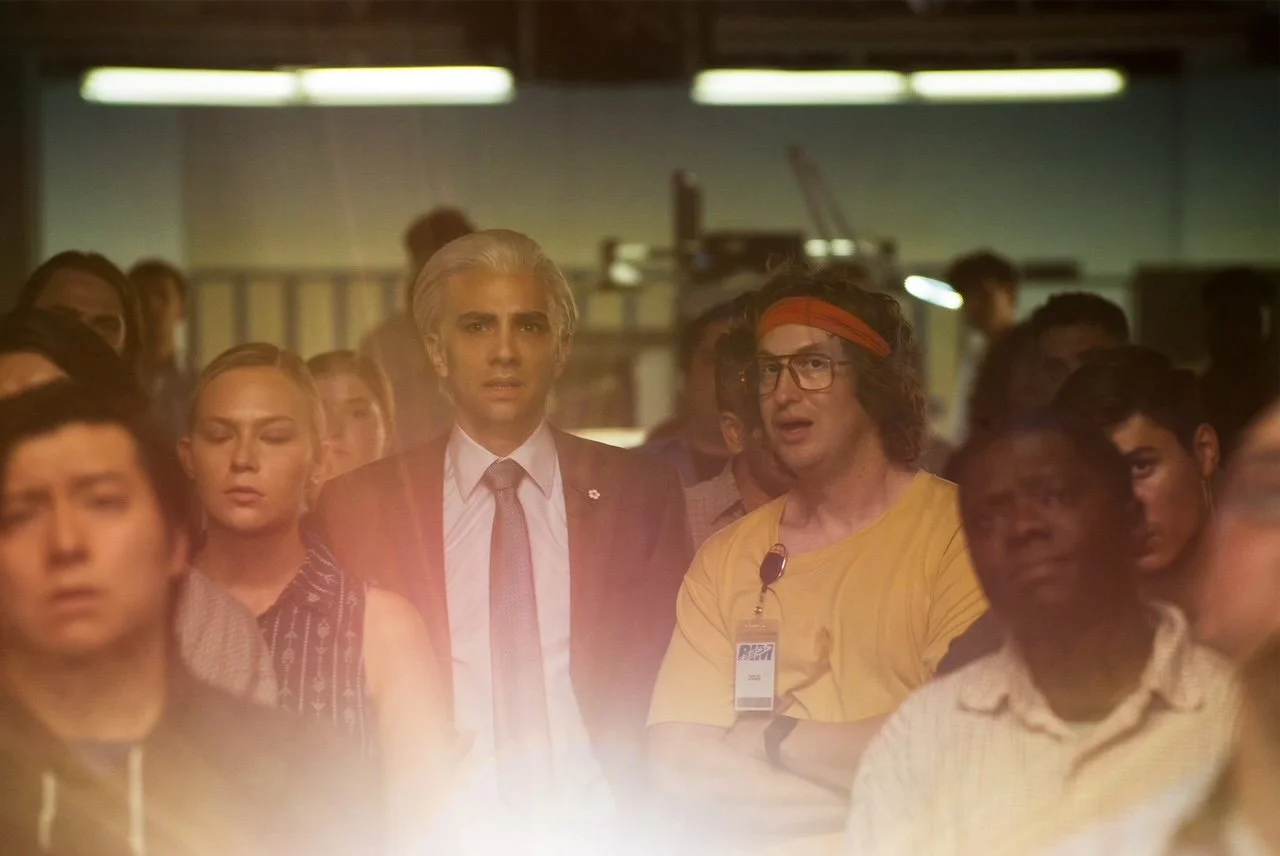

The most fascinating thing that happens during a screening of BlackBerry comes seconds after the closing credits start. That’s when everyone in the audience picks up the little $1000 computer that we all carry around with us, so we can check what’s come in while we were busy staring at a different screen for a few hours. This strictly observed ritual takes place millions of times in movie theaters across the country each year. I’m sorry to say there are plenty of people who simply can’t wait until the movie is over before worshipping at the altar of their personalized mobile device.

What makes this now-common act of servility to technology something of note when considering BlackBerry is that the audience has only seconds ago seen a story integral to explaining how things got this way. BlackBerry tells the story of, as one character in the movie puts it, the phone everybody had before they got an iPhone. Director Matt Johnson and his wonderful cast frame this story as a goofy comedy, at least until the pathos kicks in and things get unexpectedly poignant.

A new bill has been introduced in the Florida state legislature that will clamp down on what teachers are allowed to say to students when it comes to sex education. Because the kinds of people pushing draconian measures like the “Don’t Say Gay” law and the “Stop WOKE” act find it icky to think of any function involving reproductive organs beyond something that happens “down there,” this new Florida bill would naturally preclude any adult in a school setting from saying anything about menstruation to a child not yet in sixth grade. Never mind that girls can start menstruating as early as age ten.

I’ll issue this next statement in a whisper, in order to protect Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, should he read it and get the vapors: (The new movie Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. is about girls getting their period.)

Is everyone OK?

Do nothing. Stay and fight. Leave.

These are the options up for debate in Women Talking. The people debating, the titular women doing the talking, are a self-appointed committee representing all of the women in their isolated Mennonite colony that eschews modern conveniences like electricity and observes a strict patriarchal hierarchy.

The reason for their secret meetings is about as horrifying as you could imagine. It’s come to light that certain men in the colony have been using cow tranquilizers on women and girls in the community in order to rape and abuse them. They know this because one of the victims caught them in the act.

My wife fell asleep while we were watching Aftersun. It was in no way the movie’s fault; she hadn’t slept well the night before and had struggled most of the day with drowsiness. Rae found it hard to believe me when I assured her that nothing bad, traumatizing, or depressing happens over the course of Scottish director Charlotte Wells’s quietly touching debut feature.

I wasn’t lying. Nothing worse than the loss of an expensive scuba mask and a few strained moments between a father and daughter appears on the screen. Nevertheless, Wells expertly crafts a sense of dread throughout Aftersun, often barely detectable, on the edges of the frame. Her film is a marvel of delicate restraint mixed with subtle, deep emotion.

Damien Chazelle had a dream to fuse Singin’ in the Rain and Eyes Wide Shut, and, for our sins, that’s what he’s given us.

In preparation for this review, I came across a description of Babylon as drawing on “just enough real film history to flatter cinephiles and to risk their ire.” I couldn’t have put it any better myself.

Chazelle’s epic three-hour+ ode to the birth of Hollywood as a cultural phenomenon – holding sway now for a century – is by turns brilliant, exuberant, self-indulgent, exhausting, and ultimately flattens out the history of the artform Chazelle clearly cherishes. The writer/director is also so focused on giving us the spectacle and bacchanal of the last days of silent film that he forgot to write characters or a story.

Writing in 2012 as chief film critic for British daily The Times, Kate Muir observed of Chariots of Fire, for its 30th anniversary re-release, that the Oscar Best Picture winner has “a simple, undiminished power,” and that it is “utterly compelling.” Chariots of Fire makes an appearance in a critical sequence in writer/director Sam Mendes’s Empire of Light. Set roughly between the fall of 1981 and the spring of 1982, Mendes’s film is a wonderfully realized character study following the lives of the employees at a seaside British cinema. In its own way, with more humble ambitions than the Olympian scope of Chariots of Fire, Empire of Light is also utterly compelling due to its own simple, undiminished power.

Set at the fictional Empire Cinema, Light mainly follows Hilary, a shift manager at the Empire, as well as the newly hired Stephen and the rest of the theater’s staff. A bond forms between the older Hilary and the younger Stephen, and the two engage in on-again/off-again sexual trysts. Over the course of the film, we discover that Hilary has been assigned her job by the government’s social services department. She struggles with mental health issues, possibly what would today be described as severe bipolar disorder.