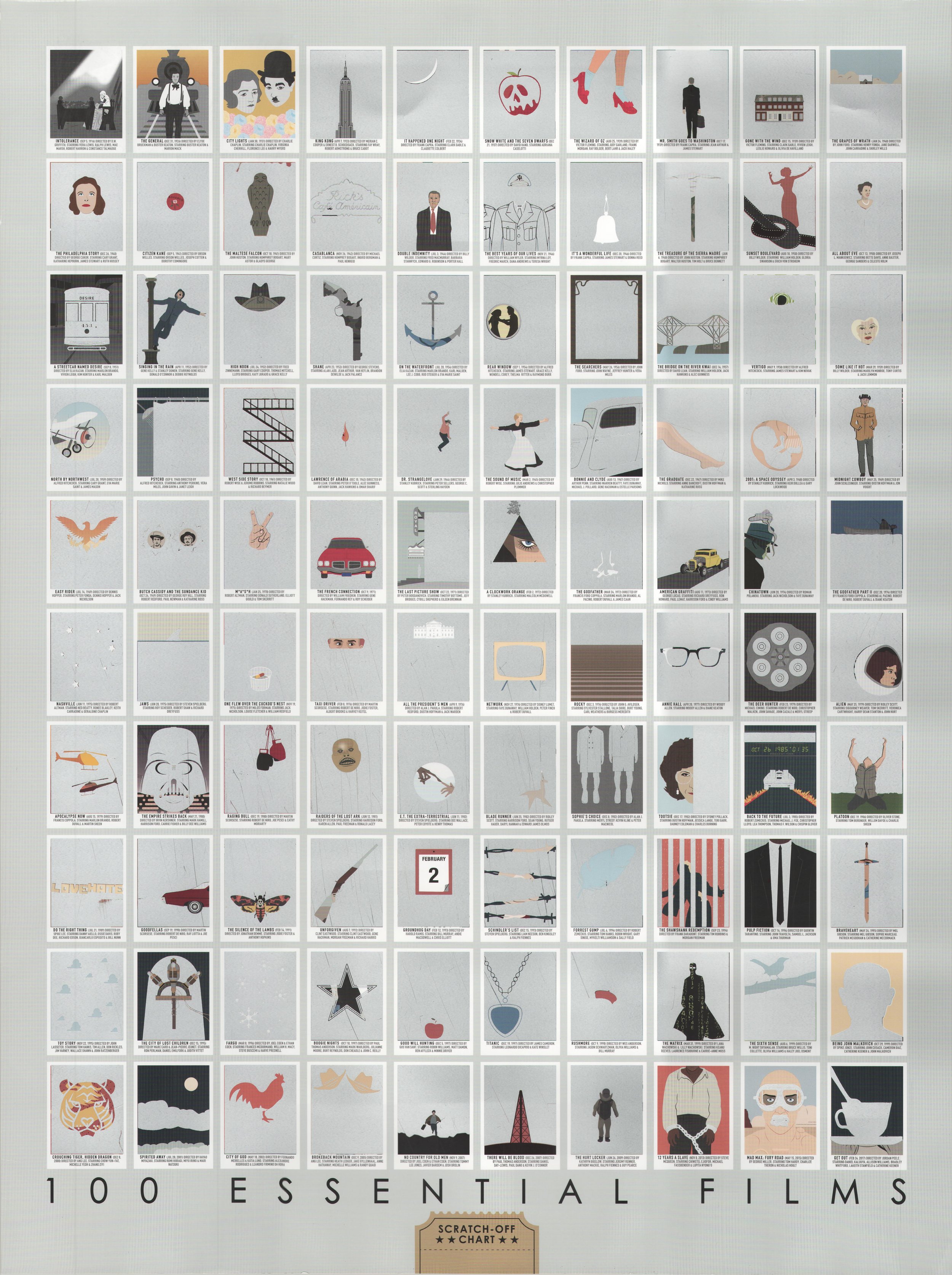

Here’s the third entry in my 100 Essential Films series. If you missed the first one, you can find the explanation for what I’m doing here. Film number three is Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. This is what many consider to be his best film, which means a lot considering Chaplin was a masterpiece machine. Just like the first two films in the series, I borrowed a Blu-ray through intralibrary loan. This edition was produced by Criterion Collection in 2013, and it looks and sounds great.

********************************

before scratch-off

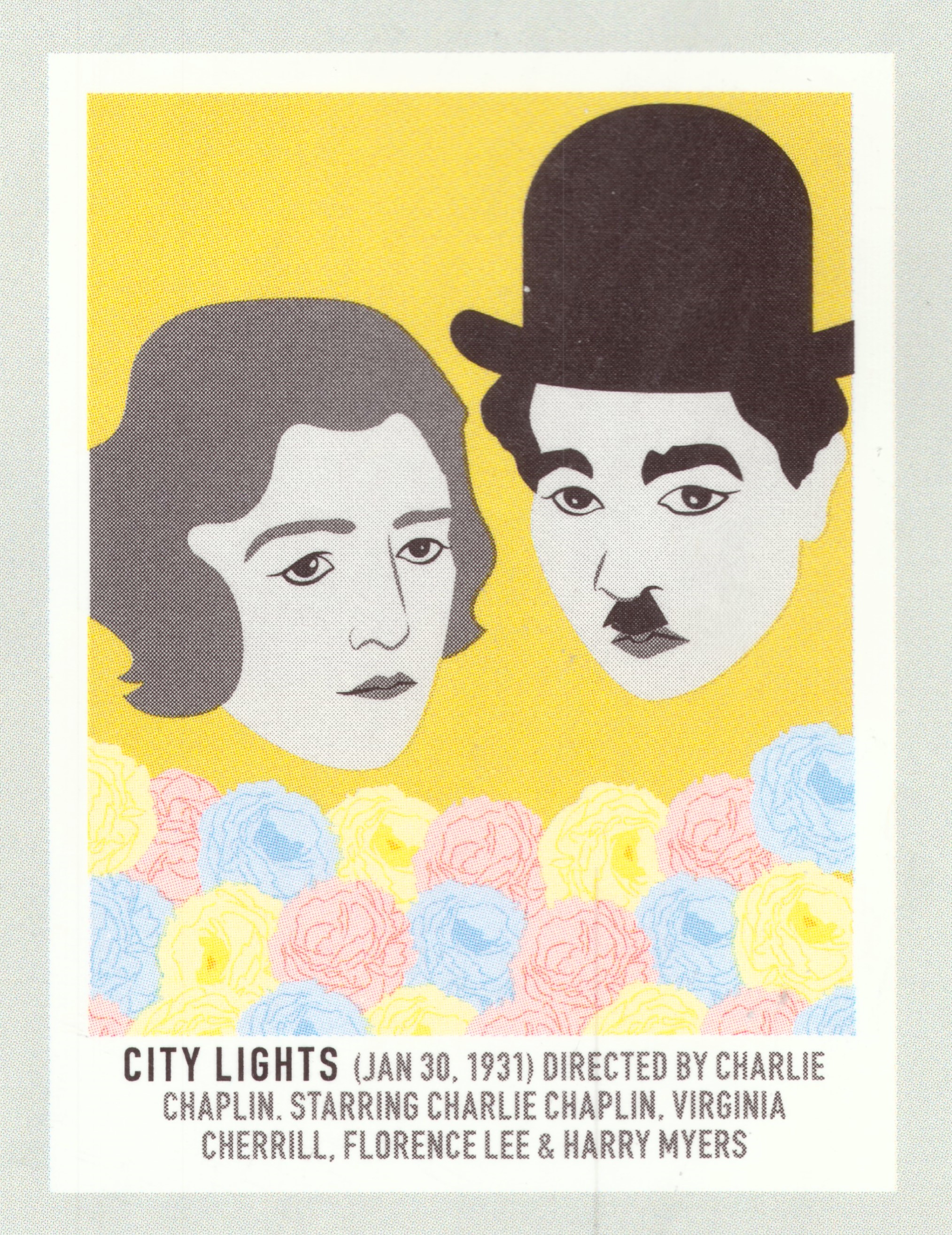

City Lights (1931)

dir. Charlie Chaplin

Rated: N/A

image: Pop Chart Lab

With the release of City Lights in 1931, Charlie Chaplin simultaneously held on to past traditions and embraced the future of cinematic technique. It’s one of the best films he ever made, proving he was as innovative as any other film artist at the time, while also reminding audiences why they fell in love with him in the first place.

A master of silent film comedy, Chaplin began work on the script for City Lights in 1928. The Jazz Singer, heralded as the first “all singing, all talking” major motion picture had just been released the year before. It promised to change the movies forever. What was Chaplin to do? Should he do what he knew best and cling to silent cinema, or should he change with the times and attempt his own first sound picture?

He decided to do both. The groundbreaking result has entertained audiences for nearly a century. While Chaplin eschewed actual spoken dialog in the movie, he incorporated myriad sound effects into his masterful sight gags. They range from the satiric – the absurd sound of kazoos standing in for the voices of pompous dignitaries as they unveil a new statue – to the downright hilarious, like when Chaplin’s hapless Little Tramp character swallows a whistle – the soundtrack is accented with the whistle every time he hiccups.

Along with those inventive effects being preserved on the new-at-the-time synchronized soundtrack, the new technology also allows us to experience another aspect of Chaplin’s brilliance. The perfectionist director also wrote the score – albeit with help on the main theme from Spanish composer José Padilla, who successfully sued Chaplin for not crediting him – and the result is delightful. The breezy, whimsical instrumentation during the boxing sequence is the best example of Chaplin’s musical prowess.

The Little Tramp keeps quiet in City Lights, and Chaplin kept a vaudeville sensibility in place to construct his shaggy dog story. Our hero moves from one hilarious, improbable scenario to the next. All of them loosely revolve around the Tramp’s attempts to win the affections of a blind woman selling flowers in the street in order to eke out a living. Early in the film she mistakes him for a man of means – the result of Chaplin’s clever stage direction of having the Tramp entering and exiting a car – and he becomes instantly smitten.

The other plot thread, involving a millionaire with a drinking problem who befriends the Tramp whenever he’s in a state of inebriation, allows the Tramp both the opportunity to help the blind woman financially and to become caught up in hilarious mix-ups.

The whole thing is a bit aimless. Chaplin repurposed one of his oldest acts – the boxing sequence – for City Lights; it does feel like it belongs in another movie. None of that matters in the slightest, though. It all hangs together magically, by turns hilarious and touching. The final scene, in which the Tramp is reunited with the blind woman after many months apart, is as touching and chill-inducing as any drama. Chaplin blends comedy and pathos in City Lights as expertly as he did old and new cinematic techniques.

after scratch-off

image: Pop Chart Lab

image: Pop Chart Lab