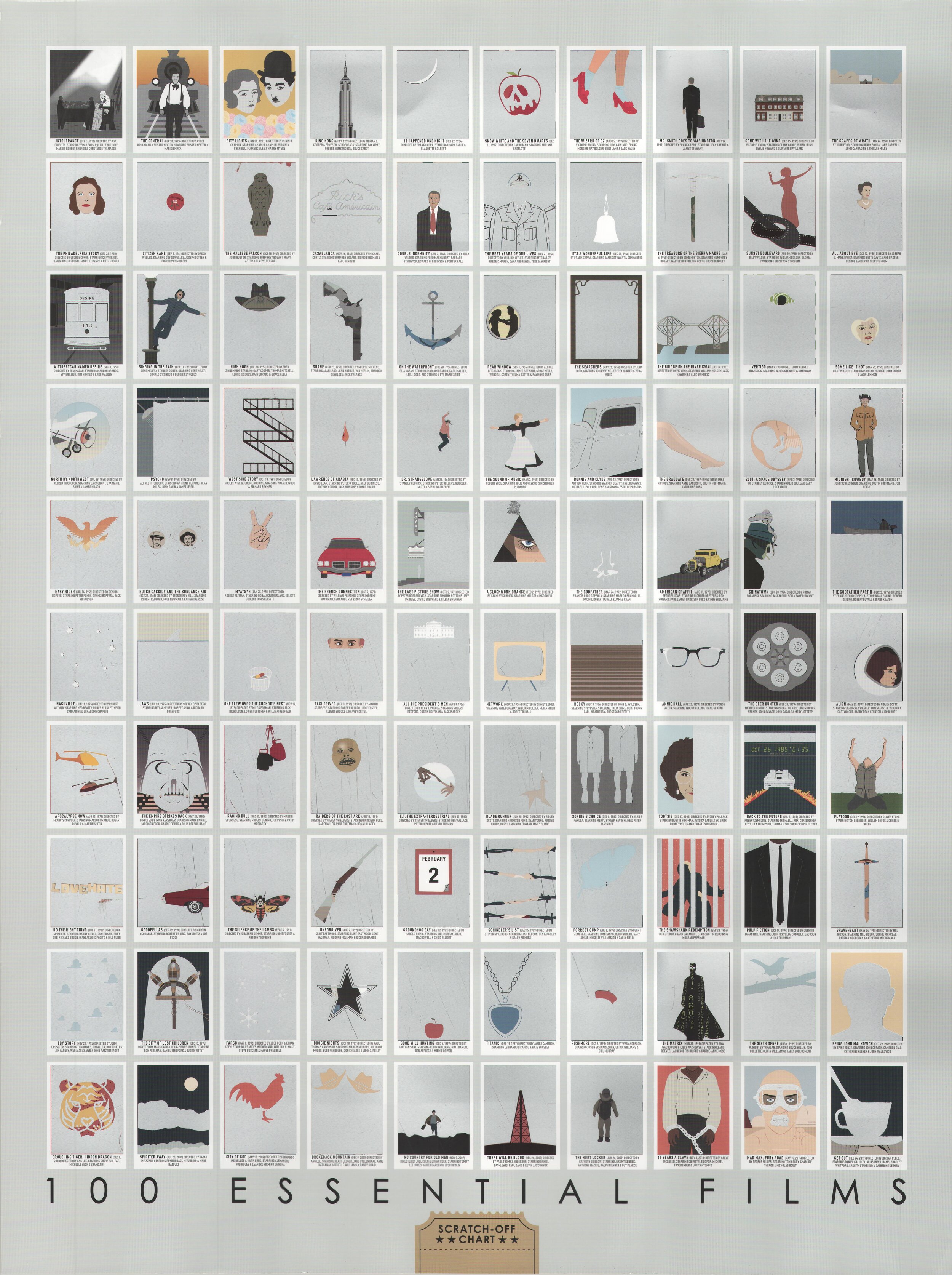

The theater closures and new release postponements caused by the coronavirus pandemic have affected my review release schedule. Because the local release of the movie I was going to write about this week has been indefinitely pushed back, I’ve been asked to hold onto my review of it until it opens here in Dallas. So, I’ve decided to take a look at the next film in my ongoing 100 Essential Films series. If you missed the first one, you can find the explanation for what I’m doing here.

Film number eight is the second in a trio of films from 1939, a banner year for movies. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is the second entry in the series from director Frank Capra (the first was It Happened One Night).

This one was a first viewing for me. While I didn’t respond to it quite as positively as I would have guessed based on its reputation, I did admire the cast, Capra’s direction, and some of the plot elements. Like every other film in the series so far, I borrowed a Blu-ray through intra-library loan (thankfully I got it before our library shut down due to a city ordinance to combat coronavirus).

I suspect this might be the first movie to showcase the proverbial “smoke-filled back room,” where political deals are hashed out among power brokers. I’m not sure, though. I haven’t had much time to do research, as I’m focusing on my social distancing. Stay safe out there!

********************************

before scratch-off

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

dir. Frank Capra

Rated: N/A

image: Pop Chart Lab

I swore to myself that I wouldn’t use the term “Capra-corn” to describe my first viewing of Frank Capra’s tale of Jefferson Smith, the good and decent hero who overcomes corrupt Washington politics. Maybe if my own cynicism wasn’t so strong, if I had seen Mr. Smith Goes to Washington fifteen or twenty years ago, I wouldn’t have been so struck by the movie’s, well, corniness. But Capra – along with screenwriters Sidney Buchman and Myles Connolly – pile on so much schmaltz that I couldn’t help but have that reaction. That’s to say nothing of the cockamamie plot turns late in the film – mostly a certain villain having an attack of conscience in the picture’s final minutes – that make the story fairly unbelievable.

The breaking point for me came when Jeff Smith – played with a prodigious amount of awe-shucks naïveté by the great James Stewart – wins over the embittered Clarissa Saunders, the aide to Smith’s predecessor in the U.S. Senate.

At the start of the film, Sen. Sam Foley has died and Gov. Hubert “Happy” Hopper chooses to appoint Smith as Foley’s replacement as a compromise between the puppet choice of political machine boss Jim Taylor, and the reform choice of the voters.

As Smith describes to Saunders the idea for his first bill, the cynical Saunders is overcome with admiration for Smith’s sincerity and decency. Capra must have used a bucket of Vaseline on the camera lens to get the extreme soft-focus close-up of actor Jean Arthur as she looks at Jeff with doe-eyed giddiness. In that moment it was a touch much in a movie that consistently, and at times laughably, wears its heart on its sleeve.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is a movie with no conception of a happy medium. Every character is either pure as the driven snow, – by the half-way point of the movie, even I wanted to figure out a way to scam Jefferson Smith – hopelessly cynical, or so irredeemably corrupt that they’ll do anything to anyone in order to ensure their machinations succeed.

Within the first fifteen minutes of Mr. Smith, the title character disappears from his first day on the job, so that he might go sight-seeing around Washington, D.C. Capra – an immigrant from Italy who moved with his family to the United States when he was five – was clearly an unabashed proponent of the idealized myths that define America.

The lengthy sequence in which Capra’s main character stands in awe of every monument in the nation’s capital, most notably the Lincoln Memorial, telegraphs Capra’s values, but does so with syrupy, and unquestioning, sweetness. It’s odd, then, when Smith goes on a punching spree a few scenes later, as he settles the score with journalists who took advantage of his naïveté to make him look like a rube in their newspaper stories.

The movie does have its charms. Despite Smith continuously failing to see people taking advantage of him, I was still in his corner. I was struck with indignation as boss Jim Taylor – in collaboration with Joseph Paine, the senior senator from the unnamed western state that he and Smith represent – scheme to take Smith down. It’s telling that a movie I kept at arms-length for most of its runtime was able to sweep me up with righteous indignation as I rooted for the hero.

James Stewart’s guileless charm as a performer is a big part of that. Jean Arthur, too, is wonderful as the hardened political lifer who can’t help but have a change of heart when she gets to know Jeff. The inimitable, stalwart actor Claude Rains is at his diabolical best as the dirty Senator Paine. A small cameo by actor Harry Carey as the president of the Senate grabbed my attention every time the old-Hollywood mainstay turned up on screen. Carey’s befuddled grin and the way he bashfully runs his hand over his face as Jefferson Smith turns the Senate upside down gave me a big smile.

What works in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is mostly due to the performers, not the material with which they are working. They were able to melt this icy-cold heart just a little, which is one of the reasons I’m so enamored of the movies in the first place.

after scratch-off

image: Pop Chart Lab

image: Pop Chart Lab