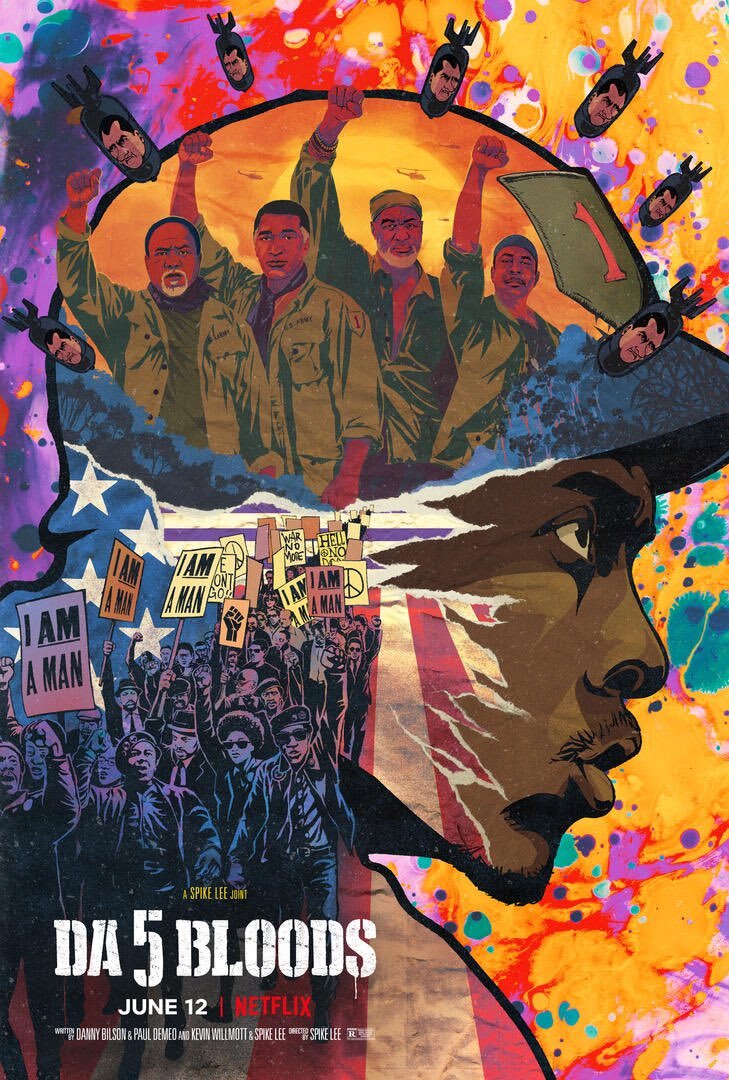

Da 5 Bloods (2020)

dir. Spike Lee

Rated: R

image: ©2020 Netflix

“Green is more important than black.” So says one of the villains of Da 5 Bloods in an exchange that leads to the movie’s action-spectacle climax. The green that the character is referring to is money – in the form of hundreds of gold bars. Da 5 Bloods is a Spike Lee joint, so it’s easy to guess what the character means when he says black. Black skin, black pride, black power, black anger. Like almost all of his work, Lee’s film is brimming with unique observations and perspectives about the black experience. This time he’s focusing on the Vietnam War, the conflict in which a disproportionate number of black men were sent to fight and die even as the struggle for black civil rights was raging at home.

Lee opens Da 5 Bloods with a virtuoso news-footage montage that brings us back in time to the late 1960s. We hear Muhammad Ali lay out his reasons for refusing to fight the Viet Cong; we see Nixon resign; it’s chaos and conflict both at home and abroad. The movie then cuts to present day Ho Chi Minh City, where we meet Paul, Otis, Eddie, and Melvin. They are the four surviving members of Da 5 Bloods, a squad of black GIs who served together in Vietnam. The men have come together for a reunion of sorts. Their goal is to find the remains of their squad leader, Norman “Stormin’ Norm” Holloway. The men are also there to locate and smuggle out of the country the cache of gold bars they hid for themselves in the mission that got Norm killed.

Da 5 Bloods is a war movie by way of exploitation film. There are hints of something like Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds with a setup reminiscent of David O. Russell’s Three Kings. At a length of over two-and-a-half hours, the shaggy-dog script’s seams start to show by the end – especially with a few egregious coincidences that help move the plot along – and the movie feels a bit cobbled together. That makes sense, because it started as The Last Tour, originally written in 2013 by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo. When director Oliver Stone dropped out of the project, Spike Lee agreed to direct after he and frequent collaborator Kevin Willmott re-wrote the script following their work together on BlacKkKlansman.

Lee’s indelible style, wit, and focus on black issues is what makes the picture as good as it is. He and Willmott have created – in collaboration with the actors portraying them – four black men who are all dealing with what the Vietnam War did to them. They do so in different ways, and Lee and Willmott explore the unique ways in which trauma affects and is expressed by those who have survived it.

Otis learns he has an adult daughter in Ho Chi Minh City, the product of a war-time romance from his youth. Eddie is the most financially well-off of the surviving squad, at least that’s the image he initially projects. Melvin is the takes-no-shit-from-nobody curmudgeon of the crew. Then there’s Paul. The most psychologically damaged of the group, Paul suffers from severe PTSD and often lashes out in anger and frustration at those around him.

It only agitates Paul further when his son, David, shows up in his hotel room. David insists on looking after his pop – and Paul insists that David get a share of the gold – as the group prepares to march into the Vietnamese jungle.

It’s telling that Lee makes the most emotionally broken of these men a Trump supporter who proudly wears his red “Make America Great Again” hat as often as possible. Early in the film, Paul talks stridently about building the wall and how Trump is looking out for people like him, as the rest of his crew looks on in puzzlement. Paul just wants what’s owed to him, and in his mind, Trump will help him get it.

I never would have guessed – especially after seeing BlacKkKlansman – that Spike Lee would make the most sympathetic character in one of his movies a Trump supporter. It was a bold decision, one that makes for often uncomfortable viewing, which, of course, is a hallmark of Lee’s filmmaking.

What makes Paul so sympathetic, though, is our understanding of the depth and breadth of his pain. The character requires an incredibly nuanced performance to translate the anguish and rage boiling inside this man. We get exactly that from actor Delroy Lindo. This is a career defining performance from Lindo, who has collaborated with Lee in three other films. As Paul, Lindo gets the only instance in Da 5 Bloods of one of Lee’s signature stylistic elements: direct address soliloquy to the camera/audience. In his confession to the camera/us/God, Paul lays bare his deepest fears and shows us his indomitable spirit.

Lee also acknowledges and explores the ways American empire, and the men who are forced into service to propagate it, has had catastrophic effects on other cultures. A key moment in the film that emphasizes this is an exchange Paul has with a Vietnamese man selling chickens. The man is unrelenting in his efforts to sell a chicken to Paul. When Paul reaches his breaking point, and begins shouting at the man to leave him alone, the vendor lashes out at Paul, accusing the veteran of killing his mother and father in the war.

Spike Lee’s film comments again and again on how the past echoes in the present through his virtuoso filmmaking style and encyclopedic knowledge of film history. His use of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries as our four heroes set off on their adventure in a Vietnamese boat pays homage to Francis Ford Coppola’s seminal Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now. We even see that film’s title in its iconic font on the wall of a club where the men celebrate their first night back together. Lee also echoes another movie about greed and gold, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, when one character says he doesn’t “need any stinking official badges.”

Da 5 Bloods also uses several different aspect ratios to shuttle us back and forth in the movie’s timeline. The first act of the film – when the men are preparing for their excursion – is shot in a very cinematic, wide aspect ratio. The flashback scenes, in which we see Stormin’ Norm (portrayed by Chadwick Boseman), are shot in the old-school, boxy Academy ratio. The scenes in the jungle, showing the men searching for Norm’s body and the hidden treasure, moves to a less wide, 1.78:1 ratio, which the movie’s distributor, Netflix, probably loved.

Lee opted to shoot his principle actors (Lindo, Clarke Peters as Otis, Norm Lewis as Eddie, and Isiah Whitlock Jr. as Melvin) in the flashback scenes complete with wrinkles and gray hair. Unlike Martin Scorsese’s heavy use of CGI to “de-age” his actors in 2019’s The Irishman, Lee lets his characters envision their past with their present selves acting it out. The technique is almost as distracting as Scorsese’s opposite approach, especially when you see the three old men interacting with the much younger Boseman as Norm.

The cinematography during these flashback sequences are, however, a highlight of the film’s aesthetic. The director of photography, Newton Thomas Sigel, gives the flashbacks a warm shot-on-film quality. Meanwhile, the present-day portion of the film is a bit too flat and has a shot-on-digital look that is underwhelming.

My other reservations with the film are plot-based ones. Like when David, Paul’s son, happens to come across some of the treasure when he goes off to dig a cathole before relieving himself. The group of men also run into a trio of people working to clear landmines – David meets the leader of this team, a French woman named Hedy, earlier in the film and flirts with her – just as they face trouble with a landmine themselves.

As unbelievable as those instances of coincidence are, that one with the landmines leads to the most riveting sequence of the whole movie. We’re not likely to see a more tense moment of filmmaking this year.

Spike Lee is in top form here with his unique visual style and unflinching social commentary – for instance, as in Apocalypse Now, Lee uses the French characters to make observations about that country’s ugly colonial history with Vietnam. His mastery of good old-fashioned entertaining storytelling makes Da 5 Bloods essential viewing in the director’s filmography, even if it doesn’t reach the heights of his masterpieces like Do the Right Thing and BlacKkKlansman.

Why it got 3.5 stars:

- Spike Lee is in top form stylistically and thematically, but some of the plot mechanics (and the fact that I felt the movie’s 154 minutes) held me back from being over the moon about it. It seems I’m an outlier; Da 5 Bloods is already getting Oscar Best Picture talk, which, despite my reservations, would suit me just fine.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- Lee and his editor, Adam Gough, do some exhilarating, almost experimental cutting in this movie. Multiple times, we see an action, then see the same action from another camera angle. In the opening, for instance, when the four men are meeting in the lobby of their hotel, two of the men throw their arms wide and engage in a big, emotional hug. We see the arms open up and the collision of bodies as the hug happens. The next cut is to a reverse angle just before the men touch each other, and we get to see the whole action again. This happens again and again in the movie, and it’s bold, bravura filmmmaking.

- The musical score for the movie is one thing that didn’t quite work for me. The never-ending sweeping, manipulative orchestrations during the battle scenes come off as overwrought.

- Spike Lee is keeping the flame burning for frequent collaborator Isiah Whitlock Jr.’s famous line reading of the word “shit” (“sheee-it”). I falsely thought Whitlock first issued the distinctive catchphrase on the series The Wire, but I was mistaken. For the whole story, see this.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- Week fourteen. I’m hearing rumblings that several theater chains are going to attempt a reopen some time in July. Time will tell.