I got up from my seat in the theater and did the math. I spent eight solid hours – a full work day – in a dark room with no windows watching Sergio Leone’s tribute to, and redefining of, the Hollywood Western genre. Most people would probably call me crazy, but I was hardly alone in the theater. There were 50 or so of us taking advantage of the special screening offered by the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema chain, which was celebrating Clint Eastwood’s 85th birthday by screening Leone’s Dollars Trilogy: A Fistful of Dollars (1967), For a Few Dollars More (1967), and the epic The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967). Three iconic films shown back-to-back-to-back, paired with all you could eat spaghetti. What did I get out of the experience, you might ask? Did I gain any new insight into the movies, myself, or life in general? I’m not sure that I did, but I can tell you I had a hell of a lot of fun either way.

Full disclosure: I’m a repertory cinema nut. It doesn’t matter if I’ve watched a movie a dozen times I will do my best to attend a new screening, especially if I’ve never seen it in a theater. A theatrical exhibition on a larger-than-life screen is an experience that no TV can ever duplicate, and I’m obsessed with experiencing movies the way they were intended. This go-round was a second chance for me to catch any of the Dollars trilogy on the big screen, after a disappointing attempt to see the final chapter at a local museum several years ago. There was an exhibition of old west landscapes paired with a double feature of the animated Rango (2011) – a really entertaining kid’s movie that I recommend – and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Naturally, I thought this an excellent opportunity to experience one of the great Westerns in a theater environment. When I arrived to discover a cramped lecture room with a screen not much bigger than my TV at home, it became my mission to rectify the experience. So, when the Alamo announced their Eastwood/Leone triple feature, I bought my ticket immediately.

A Fistful of Dollars (1967)

dir. Sergio Leone

Rated: R

image: ©1967 United Artists

My eight hour odyssey began with A Fistful of Dollars, a film that Leone spent three years defending in court before he could release it in the U.S. The litigation was due to the Western being an unauthorized and direct remake of Akira Kurosawa’s samurai drama Yojimbo, so that film’s distribution company sued. The Italian filmmaker eventually settled out of court but, luckily, the lawsuit didn’t keep A Fistful of Dollars out of theaters. Leone’s film may owe much (okay, maybe everything) to Yojimbo, but it’s undeniable that Fistful set a new standard for the classic “oater”. The plot is so high-concept it would make Michael Bay blush: A lone stranger shows up in a small town run by two warring gangs, they want to use the outsider for their own purposes, so he sets about playing one off the other. The story is incidental to the style, but that’s not a weakness, as is usually the case. To the contrary, the movie is all the better for the subversion of the old adage, “form follows function.” Leone was setting out to create a new kind of Western with Fistful. He succeeded by focusing on the mood of the movie over the plot. He also succeeded in creating a new kind of hero; one that blurred the lines between taking actions because they were morally right versus taking actions that served his own selfish purposes.

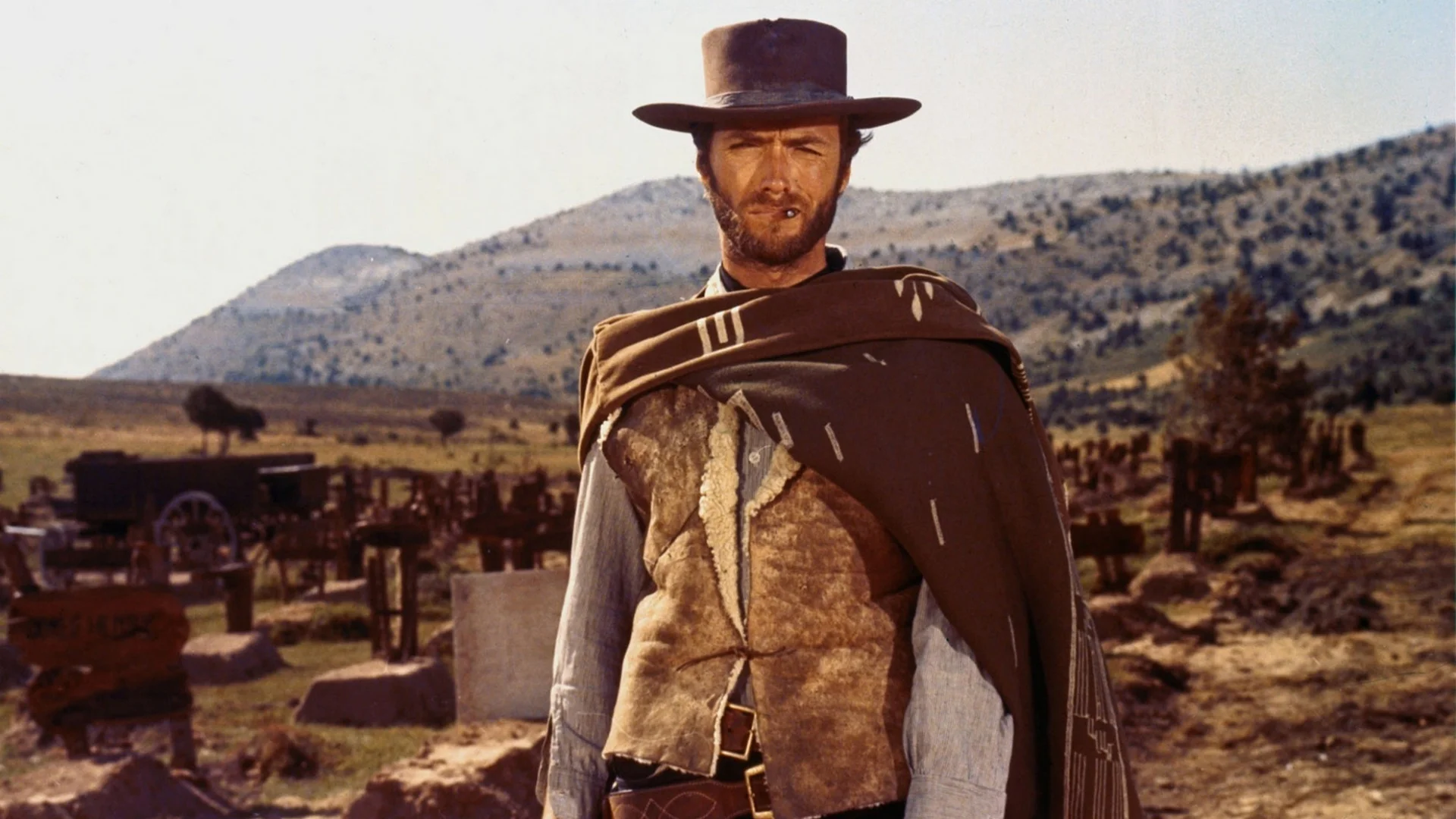

Clint Eastwood – who was known at the time only for a few B-movies and the television Western Rawhide – took the role of the nameless stranger and infused it with a sardonic sense of cool that became instantly iconic. The cold detachment he displays early in the film, as he guns down four men who refuse to apologize for laughing at his mule, establishes his sarcastic, take-no-prisoners attitude. This film made Eastwood a bona fide movie star, and it’s easy to see why.

Although it’s regarded as iconic, and rightly so, Fistful is the film in the series I’m fond of the least. When I look at the three films together, this first one comes off as slight. It’s Leone on training wheels, practicing for his masterworks to come. That’s not to take anything away from its strengths. The movie is extremely well paced. The relatively short hour and forty minute run time flew by, and at the end I was ready to dive into the next installment.

For a Few Dollars More (1967)

dir. Sergio Leone

Rated: R

image: ©1967 United Artists

For a Few Dollars More ups the ante with a more complex story than the one told in A Fistful of Dollars. It’s less of a direct sequel and more of a thematic companion. This film follows Eastwood in his efforts as a bounty hunter, and this time he actually has a name. Several people call him Manco throughout the film, and this belies the efforts by the American distributor, United Artists, to capitalize on the success of the first movie by creating a marketing campaign announcing the return of Eastwood as The Man with No Name. Complicating the movie’s plot is the arrival of Lee Van Cleef as Colonel Douglas Mortimer, a fellow bounty hunter. Both men are tracking the deadly El Indio. The way Mortimer creates his own stop on the train he’s riding in the opening scene immediately establishes that he’ll be a worthy rival to Eastwood’s character. Manco sees El Indio as just another bag of money to be collected, while Mortimer has more personal reasons for tracking the fugitive, giving the film a real emotional thrust that is lacking in A Fistful of Dollars.

The bloodthirsty criminal is played by Gian Maria Volonté with chilling insanity, like the way he seems to reach sexual ecstasy, draining his energy for a time, after each act of violence he commits. Volonté played a head honcho in one of the gangs from the first film, a practice Leone used often in this series. A handful of actors would return again and again to fill out the cast, making a strong argument that the movies are linked more thematically than with any narrative or character tissue. There is a final stand-off in Fistful that is quite satisfying, but in Few Dollars More Leone explores his favorite cinematic obsession with even more exhilaration. I’ve seen the movie half a dozen times, but the final showdown between Mortimer and El Indio never fails to quicken my pulse. For a Few Dollars More clocks in a full half hour longer than its predecessor, but Leone is so good at pacing that the added time isn’t felt. Still comfortable in the Drafthouse chair that had become my new home, I was ready to push on to the finale of the afternoon.

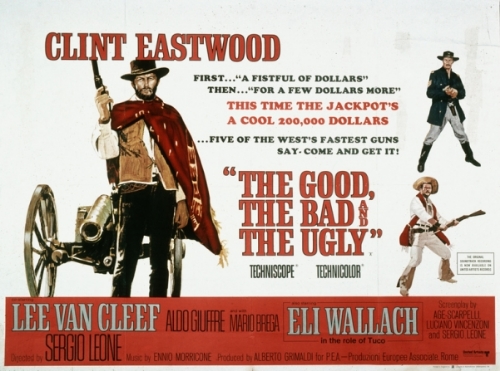

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967)

dir. Sergio Leone

Rated: R

image: ©1967 United Artists

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is Leone at his operatic best. For me, the film can be summed up in two visual techniques he uses throughout: Sweeping vistas of desert landscapes and intense close-ups of grizzled faces. The latter approach is especially effective during the several stand-offs throughout the film. Seeing how those close-ups work on the big screen gave me a brand new appreciation for them. The use of Italian countryside for the American Southwest doesn’t quite translate, but if you buy in to the story, it isn’t a problem. The third and last collaboration between Eastwood and the director finds The Man with No Name (the Good) – this time called Blondie – again collecting bounties. The twist is that now he collects them over and over on the same man: The scheming Tuco (the Ugly), played brilliantly by Eli Wallach, who has teamed up with Blondie in order to share in the reward money various towns have placed on his head.

Things change when Blondie decides Tuco’s measly bounties aren’t worth the risk, stranding Tuco in the desert and keeping all of the last bounty for himself. But all that is just the set-up, because the plot really gets going when Tuco and Blondie each hear half of a secret worth $200,000. A dying Confederate soldier tells Tuco the name of the graveyard where a cache of gold coins is buried, and tells Blondie the name on the grave holding the loot. The tale of the men being forced to work together, though neither one trusts the other, would be enough, but Leone adds more. The film still needs to fulfill the promise of its title, so enter Lee Van Cleef in a new role – the Bad. As admirable as his character was in For a Few Dollars More, Van Cleef’s Angel Eyes is every bit as despicable in this film. He learns of the buried gold through a former employer and is quickly on the trail of Tuco and Blondie. Leone isn’t content to focus on just the titular trio, though.

The events take place in the middle of the American Civil War and Blondie, Angel Eyes, and Tuco all become entangled in the struggle between the states. As brilliant as The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is, I always feel the three hours and change of its running time. As a narrative, it’s a bit episodic and some of those episodes feel out of place. The sequence concerning a dying military officer who secretly wishes for the destruction of the bridge he’s been tasked with protecting feels like an unnecessary diversion. It’s interesting and entertaining, but seems out of place in the context of a treasure hunt. Leone does know how to end a film, though, and this Western epic is no exception. This time around, he treats the audience to a three-way stand-off, perhaps the most iconic movie stand-off of all time. The editing of the sequence is masterful, cutting at an ever quickening pace between close-ups of the three men’s faces, and their hands inching ever closer toward their guns. Every time I watch this sequence, I get completely caught up in the bravura drama of the moment.

It’s hard to overstate the impact these three films had not just on the Western genre, but on moviemaking in general. Although they came near the end of the Western’s popularity – the genre would only enjoy mainstream success for another ten years or so – the style of these films fueled the beginning of a deconstructionist cycle that revitalized the category. Along with the work of Sam Peckinpah, Sergio Leone brought a more realistic, and at the same time, more over the top violent aesthetic to his films. Add to that the dizzyingly fast cuts during the action scenes, which is something that had never really been done before, and it was a combination that proved wildly popular and influential. The French New Wave gets the credit for inspiring the style of the New Hollywood movement, but Leone’s work should be recognized for its influence as well. Compare the editing of any stand-off from the Dollars Trilogy with the final shootout in the New Hollywood classic Bonnie and Clyde, which came out just a year after Good, Bad, Ugly, and the similarities are striking. The popularity and success of a film is also easily measured by the number of imitators it spawns, and these movies have literally hundreds of knock-offs. The Dollars series invented the Spaghetti Western: Italian productions about gunslingers in the American frontier.

When the credits for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly rolled (to raucous applause from the audience), I was exhausted. I collected my belongings, and made my way toward the door. I don’t know if I’m just devoted, or if I should seek professional help, because I was still ready for more. I fantasized that I had about ten minutes before the theater started up Leone’s even longer and more grandiose masterpiece, Once Upon a Time in the West. Had that been the case, I would have quickly found my way to the restroom, so I could get back to my seat and strap in for more stand-offs, and even more spaghetti.