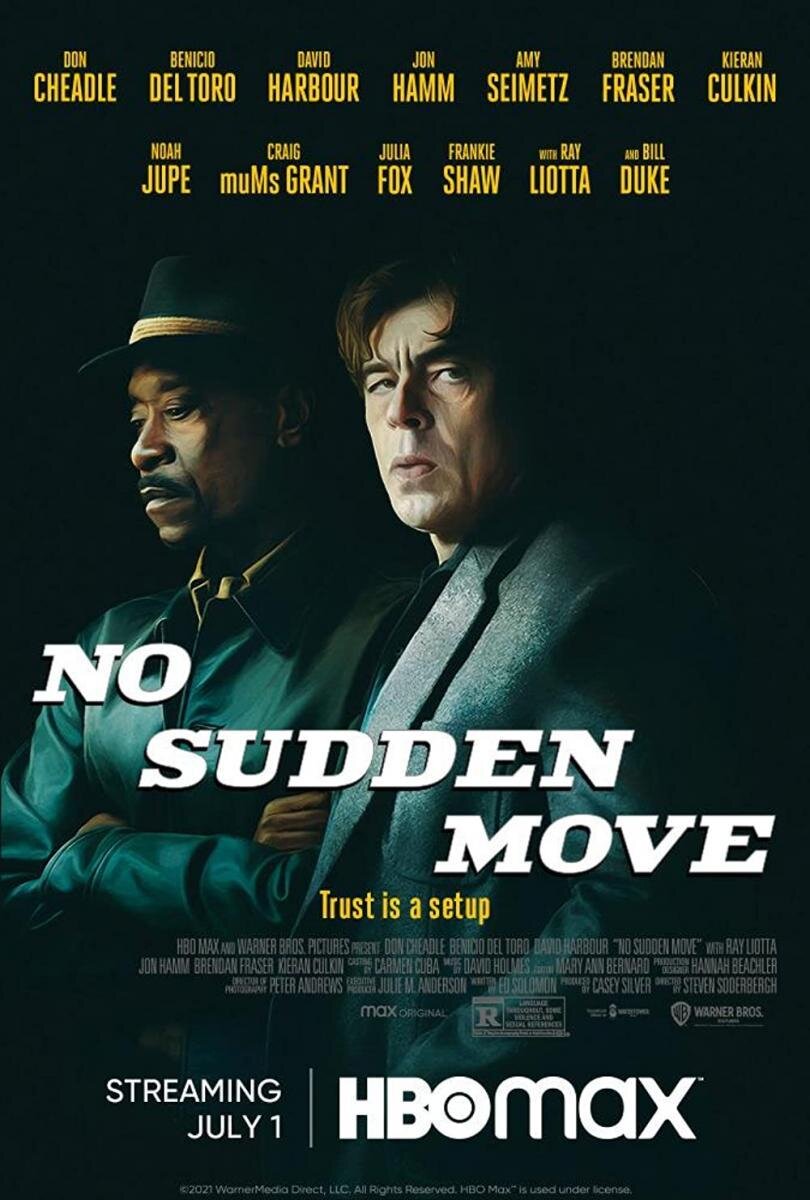

No Sudden Move (2021)

dir. Steven Soderbergh

Rated: R

image: ©2021 HBO Max

I think No Sudden Move might be great. Like, Chinatown great. I’m hedging with the “might be” – one of the worst sins a critic can commit, I suppose – because I’ve only seen Steven Soderbergh’s new noir-inflected heist movie once. As with Chinatown and The Big Sleep, the most famously convoluted noir plot in film history, No Sudden Move’s first half is so opaque as to be frustrating on first viewing. Once things started to click into place, though, especially in the climax and denouement, I began to suspect that a second viewing of the film would pay substantial dividends. Even if that’s not the case, what’s easy to see upon first viewing is Soderbergh’s masterful auteur cinematic style and the flawlessly calibrated performances from the brilliant ensemble cast.

Set in the 1950s, the film takes place over two days in Detroit. Gangster Curt Goynes, recently released from prison, needs a quick score so he can get enough cash to blow town. He’s in deep with local mob boss Aldrick Watkins. Curt stole a ledger belonging to Watkins containing decades of transactions, secrets, and damning information, and he knows he doesn’t have long before Watkins comes to collect what’s his by any means necessary.

Through a mutual associate, Curt hooks up with Doug Jones, who has a seemingly easy job for Curt. Doug is cagey as to the identity of the mastermind behind the scenes. As with any noir worth its hard-boiled salt, the job turns out to be anything but what it seems. Curt is to partner with two other men, Ronald and Charley, for a “babysitting” job. Curt and Ronald will hold a man’s family hostage while Charley accompanies this man, Matt, to the latter’s office to retrieve a top-secret document from Matt’s boss’s locked safe. If all goes well, Matt will secure the document, Curt and Ronald will let the family go, and the three stick-up men will hand the MacGuffin over to Doug in exchange for their payday.

All does not go well.

Soderbergh returns to some of his favorite preoccupations, the heist story and, specifically, the “one last job” crime film, which have proven fruitful for him in the past. While his previous work in this area, like Out of Sight, his Ocean’s franchise, and the underseen The Underneath, have all been influenced by the classic Hollywood noir style, No Sudden Move is pure neo-noir. (The director’s 2006 film, The Good German, is also an homage to noir, but I am forced to admit that I haven’t caught up with it yet.)

There are double-crosses and subplots aplenty in No Sudden Move. Matt is having an affair with Paula, his boss’s secretary. We find this out in Matt’s manic attempt to get his boss Mel’s safe combination from Paula during the heist. This was also supposed to be the day when Matt tells his wife Mary that he is leaving her for Paula. Curt’s newly minted partner Ronald is also having an affair with another man’s wife, who shall remain nameless here so as not to spoil a significant plot point midway through the film.

There are also a host of characters whose motives and actions are hazy for both audience surrogate Curt and the actual audience. Curt spends a good portion of the movie trying to figure out exactly who is behind this job. The man he’s trying to avoid, Watkins, might be involved, but it’s also likely that rival mob boss Frank Capelli is the one behind the scenes. And there’s a cop on their trail, Detective Joe Finney, whose real objective is unclear.

Screenwriter Ed Solomon, who began his career by penning the first two entries in the Bill & Ted saga and whose other credits include 1993’s Super Mario Bros., the first Men in Black, and the Now You See Me heist films, throws everything he’s got at No Sudden Move. At one point, a desperate Curt visits an old acquaintance to retrieve a very important suitcase. This woman’s connection to Curt – her reaction to his sudden appearance is a mix of frustration with and fondness for him – is never made explicitly clear. She might be a former lover, an ex-wife, or maybe even his adult daughter. There’s no mystery, however, in where her current husband stands in his opinion of Curt.

There are two reactions a viewer could have to this brief exchange (the whole encounter lasts maybe 90 seconds). You could find it frustrating and further convoluting an already deeply convoluted plot, or you could see it as adding subtle shades to the characters and world of the story, making it almost novel-like in its construction.

The issue of race complicates the whole sequence because Curt and the couple he visits are all Black. Curt and the husband exchange a few words about the neighborhood being redeveloped – the couple are moving soon – and the changing nature of Detroit. “Urban renewal,” Curt says wryly. The husband’s deadpan response implicates the racism of the time: “More like negro removal.”

It’s a throw-away moment, until the final act when the mysterious document at the middle of the heist is finally revealed. Corporate espionage and the manipulations of the wealthy and powerful, in their never-ending machinations to gain more of the same, take center stage.

In a further homage to the noir aesthetic, there’s a brilliant bit of expository villain-monologuing by the architect of the entire scheme who explains that the 1% will do whatever they must to stay in their position. Money, he explains, is almost of no consequence to men like him. When he sleeps, his money makes more money for him. In a prophetic pronouncement, he tells Curt and Ronald that any money he spends in his quest to stay at the top will always find its way back to him. In the next breath, this same character tries to distance himself from the system he and men like him have constructed. “I did not create the river, I am simply paddling the raft,” he says, disingenuously, when Curt shows a bit of righteous anger.

This all brings me back to Chinatown. A seemingly innocuous issue like clean drinking water and who controls it – which is becoming even more contentious now, in light of climate change and the extreme drought that parts of the world are starting to experience – exposes the sick and corrupt underbelly of the ruling class in that film. The MacGuffin in No Sudden Move – who wants it, and why (here’s a hint, think about the movie’s setting) – serves the same purpose.

Soderbergh, who does his usual triple duty of directing, shooting (under the pseudonym Peter Andrews), and editing (pseudonym: Mary Ann Bernard), is at the top of his stylistic game with No Sudden Move. The picture is utterly gorgeous and a delight to watch from a visual standpoint. The director uses a fisheye lens to blur and distort the outer edges of the frame, giving the world of the movie an off-kilter feel. He also uses shadow effects in the corners of certain shots to evoke the shadowy noir aesthetic, as well as canted angles, to symbolize the crooked world of his story and the inner moral turpitude of his characters. Soderbergh also uses extreme shallow focus in several scenes. It has the effect of making the characters insulated from the rest of the outside world.

One costume choice also harkens back to the noir aesthetic. They look nothing alike, but the masks that Curt, Ronald, and Charley wear during the heist are evocative of the masks worn during the heist in Stanley Kubrick’s 1956 noir film The Killing. Their similarity is more of a spiritual kinship than anything else; maybe it’s the neat suits that accompany the masks that put me in mind of The Killing.

The stellar ensemble cast of No Sudden Move, and how Soderbergh shoots them, makes the film compulsively watchable. Don Cheadle is at his rat-pack coolest as Curt. Benicio del Toro has crafted an agent of chaos persona in many of his performances – The Usual Suspects and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas come instantly to mind – and he continues that tradition here as Ronald. Kieran Culkin is a gleefully loose canon as Charley, although his character doesn’t hang around for long. Brendan Fraser is low-key hilarious as Doug Jones.

I could go on.

No Sudden Move has an incredibly deep bench of talent. David Harbour, Ray Liotta, and Jon Hamm are all a delight. There’s even a surprise, uncredited appearance from a Soderbergh regular in the pivotal role of the man behind the scenes, but it would be a travesty to spoil it.

It would be shameful if I failed to shine a huge spotlight on the legendary Bill Duke as mob boss Aldrick Watkins. Duke, a director in his own right, is best known for roles in 80s action films like Predator and Commando. He exudes – both in No Sudden Move and in life – a coolness that I suspect can’t be learned. You’re either born with it or you’re not. Soderbergh’s introduction of Duke as Watkins is a master class in establishing a character as the baddest motherfucker in the room. Every move or word from Duke throughout the movie is given the weight of that introduction.

Soderbergh and Solomon gave themselves an out with regard to female characters by way of their 1950s testosterone-soaked noir setting. The women in No Sudden Move are given woefully little to do, with the exception of Julia Fox as a minor femme fatale. The decision makes the movie less well-rounded than it otherwise could be.

So, is No Sudden Move a great movie, like Chinatown? A movie steeped in the noir tradition that is meticulously plotted with a satisfying payoff? Or is it an opaque, convoluted mess that only pretends to profundity? I’ll let you know after my second viewing.

Why it got 4 stars:

- Between the ones I’ve seen and what I’ve read about the ones I haven’t, No Sudden Move is Soderbergh’s best work in a decade, since 2011’s Contagion. His style here is in top form, and despite my reservations about its confusing nature, I think it will age well over time.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- Is it me, or is No Sudden Move a completely forgettable title?

- The first minute or so is a wonderful example of setting the stage. As we walk behind Curt down a Detroit street, the film cuts to black-and-white photos of his past.

- There is a character in this movie named Paula Cole. Thousands of people from my generation probably raised a quizzical eyebrow when they heard the name while watching the movie, like I did.

- There are some moments of truly weird comedy here. While I laughed at almost every one – David Harbour announcing to his boss that he’s about to physically assault him if he doesn’t hand over the document is one. “I’m about to punch you. This is a punch.” – I don’t know if they all work with the overall tone of the movie.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

No Sudden Move is streaming exclusively on HBO Max.