I’ve definitely become more cynical in the decade since I started writing regular movie reviews. I’m sure of it after my reaction to seeing Jason Reitman’s new paean to the comedy institution known as Saturday Night Live. Reitman’s film, Saturday Night, is enjoyable enough as a peek behind the curtain at the madcap goings-on in the lead up to the first episode of what would become the longest running sketch comedy show in television history. It’s also cliché-ridden, offers practically zero insight into any of the characters, and features a made-to-order climax wherein everything magically falls into place at exactly the right moment. An exercise in subtlety, it is not.

Viewing entries in

Biopic

I’m not sure if the title of the new film from Bradley Cooper, Maestro, is supposed to refer to the movie’s subject, legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, or to Cooper himself. Because make no mistake, Bradley Cooper is the definitive maestro in control here, and he wants you to know it; as with A Star is Born, Cooper’s debut behind the camera, the actor-turned-director is pulling double duty as both director and star. The results this time around are a decidedly more mixed bag.

With Oppenheimer, filmmaker Christopher Nolan has made nothing less than the Lawrence of Arabia of the 21st century. Like David Lean’s 1962 masterpiece, Nolan’s picture is epic and grand in both scope and scale, while delicately humanizing a figure about whom most of the populace – myself included, at least, until I saw the movie – know little-to-nothing.

While the grandeur of recreating the first human-made atomic reaction has transfixed media coverage and those anticipating the film’s release, Oppenheimer’s true triumph is in unlocking the mystery of the man. By the time we reach its conclusion, Nolan’s film has given us a crystal-clear understanding of who J. Robert Oppenheimer was. We understand what drove him to unleash an unimaginable weapon upon mankind and how that work tortured him for the rest of his life.

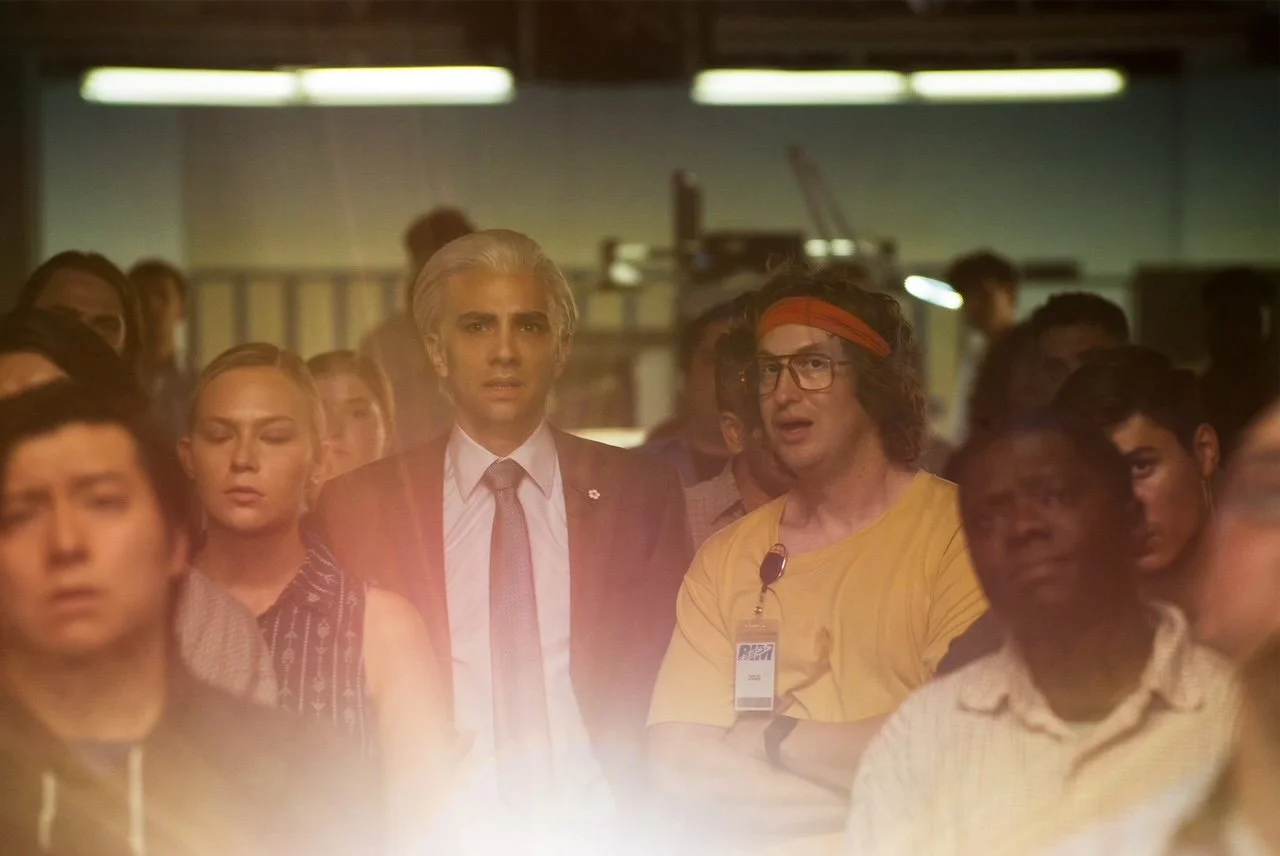

The most fascinating thing that happens during a screening of BlackBerry comes seconds after the closing credits start. That’s when everyone in the audience picks up the little $1000 computer that we all carry around with us, so we can check what’s come in while we were busy staring at a different screen for a few hours. This strictly observed ritual takes place millions of times in movie theaters across the country each year. I’m sorry to say there are plenty of people who simply can’t wait until the movie is over before worshipping at the altar of their personalized mobile device.

What makes this now-common act of servility to technology something of note when considering BlackBerry is that the audience has only seconds ago seen a story integral to explaining how things got this way. BlackBerry tells the story of, as one character in the movie puts it, the phone everybody had before they got an iPhone. Director Matt Johnson and his wonderful cast frame this story as a goofy comedy, at least until the pathos kicks in and things get unexpectedly poignant.

You might be forgiven, especially considering Hollywood’s reputation, for expecting a movie titled Tetris to behave more like the 2012 screen adaptation of the popular board game Battleship and less like an intricately plotted spy picture, an 8-bit Bond. Thanks to Noah Pink’s tightly paced screenplay, Jon S. Baird’s crowd-pleasing direction, and a true story that the pair embellished in order to make it sing on the big screen, 8-bit Bond is what we get. Tetris is a raucous good time. It also has more on its mind than how seven geometric game pieces might fit together.

The key moment in Baz Luhrmann’s latest cinematic maximalist bacchanal – about the one and only King of Rock and Roll, Elvis Presley – comes within the picture’s first five or ten minutes. The internet meme culture overlords got it immediately. It’s the scene, which became a viral sensation, of Tom Hanks’s Colonel Tom Parker being informed that the voice he’s hearing on the radio, Elvis singing That’s All Right, belongs to a white man. “He’s white…,” Hanks’s Parker says as if in a trance; it’s half-question, half-stunned-declarative-statement.

Col. Tom – who represented Presley from 1956 until the singer’s tragic death in 1977 and helped himself to over half of everything Elvis earned – is our (not so) humble narrator. He acknowledges that some will consider him “the villain of this here story.” Luhrmann let’s Col. Tom have his say, but he also uses his strong directorial hand to make sure we see the one-time carnie’s legacy of selfish and cruel behavior and the role it played in Elvis’s descent into addiction, despair, and, ultimately, death.

As you might imagine, a semi-autobiographical movie about one of the most respected and revered filmmakers ever produced by the Hollywood system is itself paying homage to the art form that birthed it. The pivotal sequence of The Fabelmans, in which the young protagonist Sammy Fabelman – based loosely on director Steven Spielberg’s own formative years – uncovers a family secret, is straight out of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 arthouse sensation Blowup. In that film, a photographer becomes convinced that he has captured a murder with his photography.

In The Fabelmans, Sammy has captured, through his obsessive moviemaking, his mother’s infidelity. As Sammy scrutinizes each frame, each stolen touch between his mother and Bennie, the man he thinks of as an uncle, he realizes that his idyllic family life is built on a lie.

Every time I hear one of a select group of pop hits from the last 40 years, I start singing the wrong words. They might be lyrics about the Star Wars character Yoda, when the song is actually about a woman named Lola. They might be lyrics about making prank phone calls when the song is really about chasing waterfalls. Every time this happens – and I mean every. single. time. – my wife rolls her eyes and threatens to divorce me.

I will never stop, though, because I am a lifelong "Weird Al" Yankovic fan. My music collection contains every album from the most successful and famous parody-song artist of all time, save two. (The last one I obtained was 2006’s Straight Outta Lynwood, so I’m missing 2011’s Alpocalypse and 2014’s Mandatory Fun.)

All that to say I might not be the most impartial judge of a movie about – and co-written by – Yankovic. The new film, Weird: The Al Yankovic Story, directed by comedy writer and filmmaker Eric Appel, in his feature debut, is an absolute hoot. Take my opinion with a grain of salt, since I was clearly in the tank for it from frame one, but Weird is the goofiest, most ridiculous, funniest comedy of the year.

King Richard is a tidy movie. It hits every basic beat you expect an underdog sports movie to hit. There’s adversity and struggle followed by determination and the beginning signs of success before a climactic test of will and talent as the grand finale. Like another soaring sports movie with an unexpected ending – think of a sport that’s fallen out of favor in modern times – how the characters react when things don’t go as planned is what gives the picture its true strength and inspiration.

As with his 2016 film, Jackie, director Pablo Larraín has crafted another emotionally charged fable centered around a powerful woman and the impossible circumstances in which she finds herself. I use the word fable to describe Spencer because that’s how the movie describes itself in its opening seconds. “A fable from a true tragedy,” are the words we see as the movie begins. It’s a clever way for Larraín and screenwriter Steven Knight to immunize themselves from charges of historical inaccuracy.

The word fable also readies Spencer’s audience for something fantastical. Larraín has made a biopic by way of psychological horror here; his picture attains an emotional truth by tying its point of view to the heavily subjective mental and emotional state of its protagonist, Diana, Princess of Wales.

The radiant and talented actor Jessica Chastain probably saw a certain little gold statue in her future when she bought the rights in 2012 to Tammy Faye Bakker’s life story. There’s nothing the Academy loves more in a best performance category than an actor radically altering her or his appearance for a role: Robert De Niro as Jake La Motta in Raging Bull; Charlize Theron as serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Monster; Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf in The Hours. Oscar really loves it when beautiful people are perceived as uglying themselves up for a role.

Chastain certainly fits the bill with her performance as disgraced televangelist Bakker in the dramedy The Eyes of Tammy Faye. The phosphorescent makeup and wild hair styles that were Bakker’s trademarks make Chastain practically unrecognizable – especially in the latter parts of the film.

Judas and the Black Messiah is like a drink of water after days in the desert. It exists and was made to upend the kind of fascistic patriotism that demagogues like Donald Trump and the recently departed Rush Limbaugh wallow in like so many pigs in shit. While their ilk pushes a cretinous version of history that worships power and the violence that flows from that power, truth-tellers like director Shaka King and screenwriters Will Berson and the Lucas brothers are making art that exposes state-sanctioned terror.

King has also made a riveting morality tale about loyalty and betrayal within a revolutionary movement. His picture is incendiary and features performances from two of the best actors working today, Daniel Kaluuya and Lakeith Stanfield. Kaluuya and Stanfield’s performances couldn’t be more different, but they are both wonders to behold, each in their own way.

“You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression.”

So says Herman J. Mankiewicz early in the biopic about his greatest professional achievement, writing the screenplay for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Mank, that’s precisely what director David Fincher does with Mankiewicz. Here was a man of principle, Fincher shows us. Here was a man of character. Here was a drunk, an inveterate gambler, but above all, here was a man with an absolute conviction in what he believed.

The Julie Taymor who directed the electric films Titus, Frida, and, yes, even Across the Universe – a movie which wasn’t well received by most critics, but which really worked for me – shows up a little over an hour into her latest effort, The Glorias, the biopic about journalist and activist Gloria Steinem.

There are Taymor flourishes in the meandering first 70 minutes of the picture, to be sure. The film opens with a sequence in which an older version of Steinem – four actresses play the iconic feminist throughout The Glorias – looks out the window of a Greyhound bus as it rolls along the highway. Steinem and everything inside the bus are in black and white, everything outside the bus is in full color. It sets an interesting aesthetic that doesn’t pay off until Steinem finds her fiery passion for the Women’s Liberation movement. That’s when the movie really starts to rip.

In the opening scenes of Shirley, central character and audience surrogate Rose Nemser meets the writer Shirley Jackson at a house party. Rose and her husband, Fred, will be houseguests of Jackson and her husband, literary critic and Bennington College English professor Stanley Edgar Hyman, while the newlywed Nemsers look for their own place. Fred has just accepted a job in the English department at Bennington, and Stanley is to be Fred’s mentor.

Upon their meeting at the party, Rose compliments Shirley’s recently published short story, The Lottery. She tells Shirley that reading it “made me feel thrillingly horrible.” There is no more apt description for my own emotional state while watching Shirley. It is a thrillingly horrible experience, perhaps the best movie I’ve seen so far this year. Any fan of Shirley Jackson’s work should be entranced by it.

Can You Ever Forgive Me? is for everybody out there who feels like a complete fraud. The movie is based on writer and literary forger Lee Israel’s confessional memoir. When her career as an author of celebrity biographies stalled due to lack of critical or commercial success, Israel got desperate. She spent a year in the early 1990s forging letters by dead celebrities like Noël Coward and Dorothy Parker and selling them to autograph brokers for hundreds of dollars each. The film is ostensibly about Israel successfully flimflamming the entire literary document community before the FBI caught onto her. But it’s also an examination of her sense of identity being stripped away when what she’s built it on – her work as a writer – is destroyed because both her colleagues and the public tell her she’s no good at it.

If you couldn’t tell from the opening sentence of this review, I count myself as one of those people who feels like a fraud.

We all have that acquaintance, friend, or family member who use their Facebook profile solely to antagonize members of their social circle whom they consider their political enemies. These are almost always people who would never do the same thing in a face to face setting. They like to “start shit,” but from the safety of their phone. These people are a shade different from what are popularly known as internet trolls, because they believe in the opinions they’re expressing, so it’s not 100% about getting under their target’s skin. It’s only 75% about that. Vice, Adam McKay’s inflammatory, obnoxious biopic about Dick Cheney, arguably the most destructive vice president in American history, is the cinematic equivalent of these true-believer assholes.

There’s been plenty of digital ink already spilled about Green Book being a White Savior Film. While I’ll also spill a bit of my own on the topic, there isn’t much I can add. For me – an average white dude who’s seen his fair share of movies – the most glaring fault about the picture, a dramedy dealing with race relations in the Jim Crow era, is the paint-by-numbers feeling of it all. This is a movie that strives to hit every standard beat in the uplifting “inspired by a true story” template. As an exercise in mediocrity that serves up something we’ve all seen dozens of times before, Green Book is an unparalleled success. It’s utterly predicable and is the kind of movie that would have felt fresh had it been made 20 or 30 years ago. Still, for all it’s flaws, Green Book isn’t entirely without its charms. In addition to a superb turn from actor Mahershala Ali, the movie does provide some inspiring moments and a message about race that plenty of people still haven’t absorbed.

On the Basis of Sex stresses that its subject, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, is uncompromising and unmatched when it comes to the mastery of her chosen profession. The film is right to do so. In 1956, Ginsburg was one of just a few women admitted to Harvard Law School, and she graduated at the top of her class at Columbia after transferring there so her husband could take a job in New York City.

She later used a unique case – the focus of the film – to challenge the constitutionality of legal gender-based discrimination. She would eventually reach the pinnacle of American jurisprudence when she was confirmed to the United States Supreme Court. It’s disappointing, then, that the cinematic tribute to such a historically significant, dynamic figure like Ginsburg should be as middling as it is. On the Basis of Sex tries to cover too much ground in its first half, and the picture only really hits its stride in the last act. It’s a biopic that covers a vital individual in an unsatisfying, if entertaining, way.

It appears that the opioid crisis has finally reached far enough beyond fly-over country for Hollywood to notice it and feature it as the social problem of the moment. Two awards season hopefuls showcase not just drug addiction, but the kind of drug addiction that has been making headlines for almost a decade now. Both Beautiful Boy and Ben is Back focus on men in their early 20s who are opioid addicts and how their parents struggle to help them break free of the addiction.

I have no opinion yet on Ben is Back, because I haven’t seen it as of this writing (although the screener is sitting on my desk in the “to watch” pile) but looking at the cast and a brief plot synopsis, I’m willing to venture a guess that it shares the same problem Beautiful Boy has. While the picture achieves what it sets out to do, Beautiful Boy is, if you’ll pardon the expression, the easy way of exploring the devastating opioid epidemic.