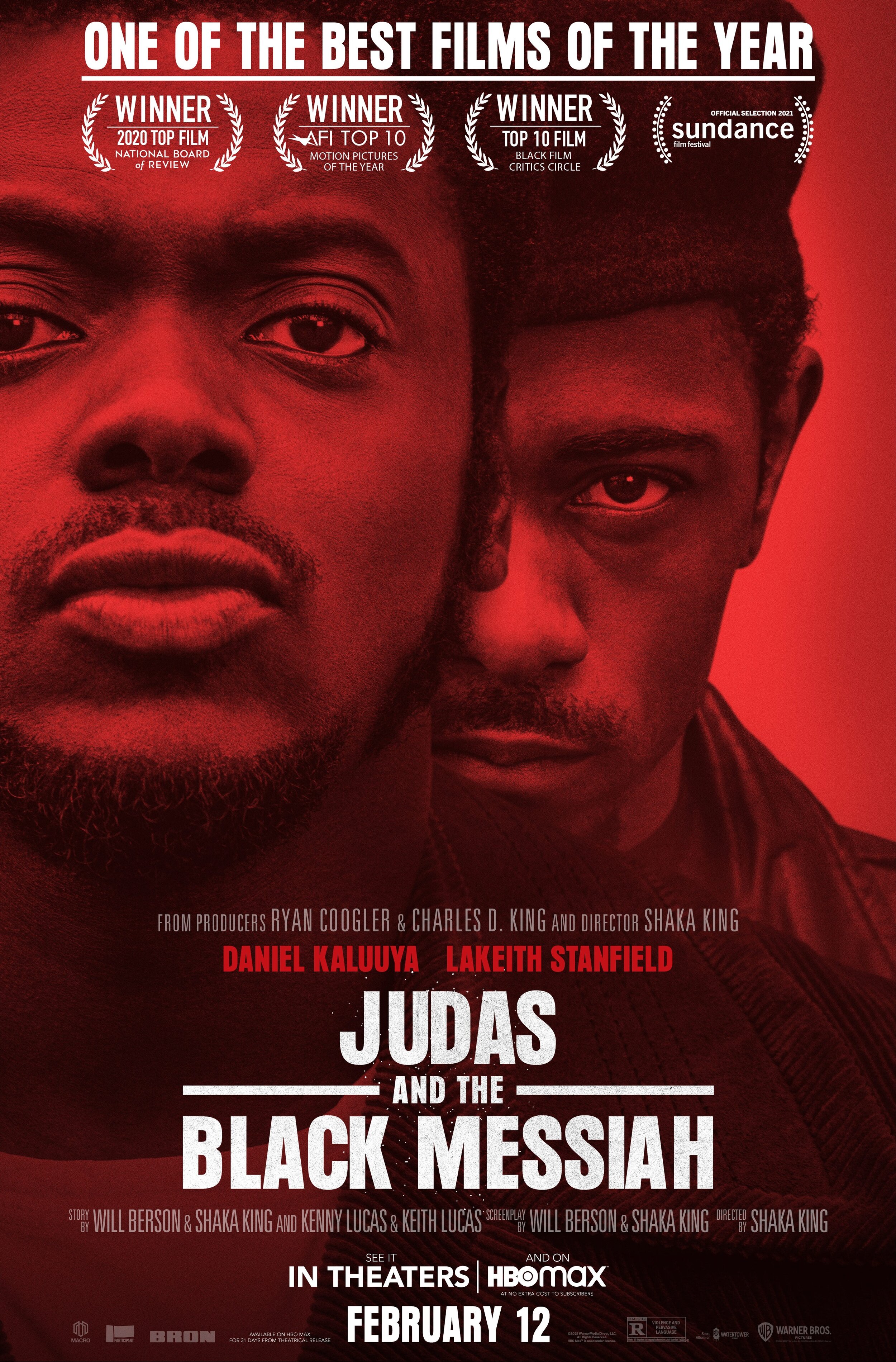

Judas and the Black Messiah (2021)

dir. Shaka King

Rated: R

image: ©2021 Warner Bros. Pictures

Judas and the Black Messiah is like a drink of water after days in the desert. It exists and was made to upend the kind of fascistic patriotism that demagogues like Donald Trump and the recently departed Rush Limbaugh wallow in like so many pigs in shit. While their ilk pushes a cretinous version of history that worships power and the violence that flows from that power, truth-tellers like director Shaka King and screenwriters Will Berson and the Lucas brothers are making art that exposes state-sanctioned terror.

King has also made a riveting morality tale about loyalty and betrayal within a revolutionary movement. His picture is incendiary and features performances from two of the best actors working today, Daniel Kaluuya and Lakeith Stanfield. Kaluuya and Stanfield’s performances couldn’t be more different, but they are both wonders to behold, each in their own way.

Judas tells the story of Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s. Hampton and his goal of Black liberation were seen as a domestic terror threat by no less than the head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover. At the behest of Hoover, FBI special agent Roy Mitchell recruits petty criminal Bill O’Neal to infiltrate Hampton’s Black Panther chapter, after O’Neal is arrested for impersonating a federal agent in an attempt to steal a car. O’Neal agrees to become an FBI criminal informant – not that he has much choice – and begins spying on Hampton and the Black Panthers for Mitchell.

No one should sleep on the style and expert craft of Shaka King’s direction. This is only King’s second feature, after 2013’s Newlyweeds, in addition to the dozen episodes of television he has directed. King shares a writing credit for the taut screenplay with Will Berson, and both men share a story credit alongside brother writing team Kenny and Keith Lucas. Berson and the Lucas brothers were working on Hampton scripts separately, but they teamed up when one of those projects fell through.

There is an authenticity to the late- ‘60s setting that King and production designer Sam Lisenco have created here. Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt gives the movie a gritty look that’s fitting for inner-city Chicago. That’s where Hampton did his work to help struggling Black people, like with the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast for Children program. He also did consciousness raising about the oppression that the Black community was enduring at the hands of the white power structure.

At the center of Judas and the Black Messiah are two magnetic lead performances.

The charismatic Daniel Kaluuya is a force of nature as Fred Hampton. I sat in wonder of Kaluuya’s overpowering screen presence during the “I am a revolutionary” speech segment of the film. There is a lot of bombast to Kaluuya’s Hampton; it’s an effective technique to draw attention to the blatant injustice Hampton faced and that Black people are still fighting today.

Kaluuya’s performance is anything but one-note, however. When he’s not standing in the spotlight, making impassioned speeches, Kaluuya shows us the quieter, contemplative side of Hampton. We see a man totally dedicated to the cause of Black liberation.

There is also a love story at play in Judas, as Hampton fell in love with fellow Black Panther Party member Deborah Johnson. I wasn’t initially convinced of this sub-plot; I thought it was a tacked-on attempt to further humanize Hampton. I was wrong. We are given real insight into both characters, especially through Dominique Fishback’s performance as Deborah Johnson. The anguish that Fishback telegraphs when Hampton prophesies his own death during a speech is heartbreaking.

Lakeith Stanfield gives a nervous, jumpy performance as the Judas of the title, FBI criminal informant and Black Panther infiltrator Bill O’Neal. Via Stanfield’s expert interpretation, we are painfully aware of the impossible position that the FBI forced O’Neal into when he had to choose between prison for grand theft auto or spying on the Black Panthers. The movie gives us an idea of just how terrifying this situation is when O’Neal explains to his FBI handler, Agent Mitchell, why he impersonated an FBI agent as his ruse to steal the car: “A badge is scarier than a gun.”

Stanfield is consistently brilliant throughout Judas, but one scene in particular stands out. At one point, a few of the Black Panther members become suspicious of O’Neal’s true motives and his new car – the car is a gift (or down-payment) from the FBI for O’Neal’s informant work. One member pulls a gun on O’Neal and demands to know where he got the car. Stanfield, as O’Neal, goes into a stammering explanation, where it sounds like the actor flubs several of his lines. He makes O’Neal’s panic so real in this moment that it seems like Stanfield is breaking character. It’s a brilliant decision and a display of just how good Stanfield is.

The supporting cast for the film complements the two leads wonderfully. Jesse Plemons has crafted a niche for himself as simultaneously bland and unassuming yet menacing in roles like Todd for the television series Breaking Bad and as the lead in last year’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things. He does the same here as O’Neal’s FBI handler, Agent Mitchell.

The legendary Martin Sheen shows up under a mound of prosthetic makeup to portray the paranoid, racist FBI director. Sheen goes full tilt as Hoover. In one scene, Hoover asks Mitchell what the younger FBI agent will do when his infant daughter some day brings a “negro man home for dinner.” It’s an effectively sickening moment from Sheen; it was hard to hear those words come out of President Jed Bartlett’s mouth, but I’m sure Sheen relished the role as a way to further cement Hoover’s ignominious place in history.

Judas and the Black Messiah is bookended by interviews that O’Neal gave for the PBS documentary about the civil rights movement that aired in the late 1980s, Eyes on the Prize. It’s an effective way to emphasize the demons that O’Neal struggled with when he began to believe in the movement which he was also betraying. There are a lot of expositional title cards in the coda to the film that takes some of the dramatic punch out of its climax, but it doesn’t dampen the visceral experience of the movie up to that point.

Shaka King has made a powerful film about loyalty and treachery and the continuing struggle for Black self-determination. In the wake of the George Floyd protests of last summer, which drew attention to state-sanctioned violence and murder perpetrated against Black people, King’s movie is as timely as ever.

Why it got 4 stars:

- Judas and the Black Messiah is taut storytelling with a moral that, although the movie is set 50 years ago, is still very relevant to today. Top all that off with some outstanding performances, particularly from the two leads, and that makes this one hell of a good movie.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- There is a perfect moment of juxtaposition early in the film when we see O’Neal’s shabby apartment smash cut to a shot of Agent Mitchell’s beautiful and well-appointed home.

- Agent Mitchell: “You can’t cheat your way to equality.” But you can, as the movie makes clear, cheat your way to supremacy…

- Mark Isham and Craig Harris’s tense score for the film adds the right touch of menace and foreboding to the action.

- There is a heartbreaking scene late in the film in which Hampton delivers a monolog about Emmett Till’s murder and the moment he realized there were people who wanted to do the same thing to him simply because of the color of his skin.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- Judas and the Black Messiah is playing in select theaters and is available to stream with an HBO Max subscription (which is how I screened it) through March 14th.