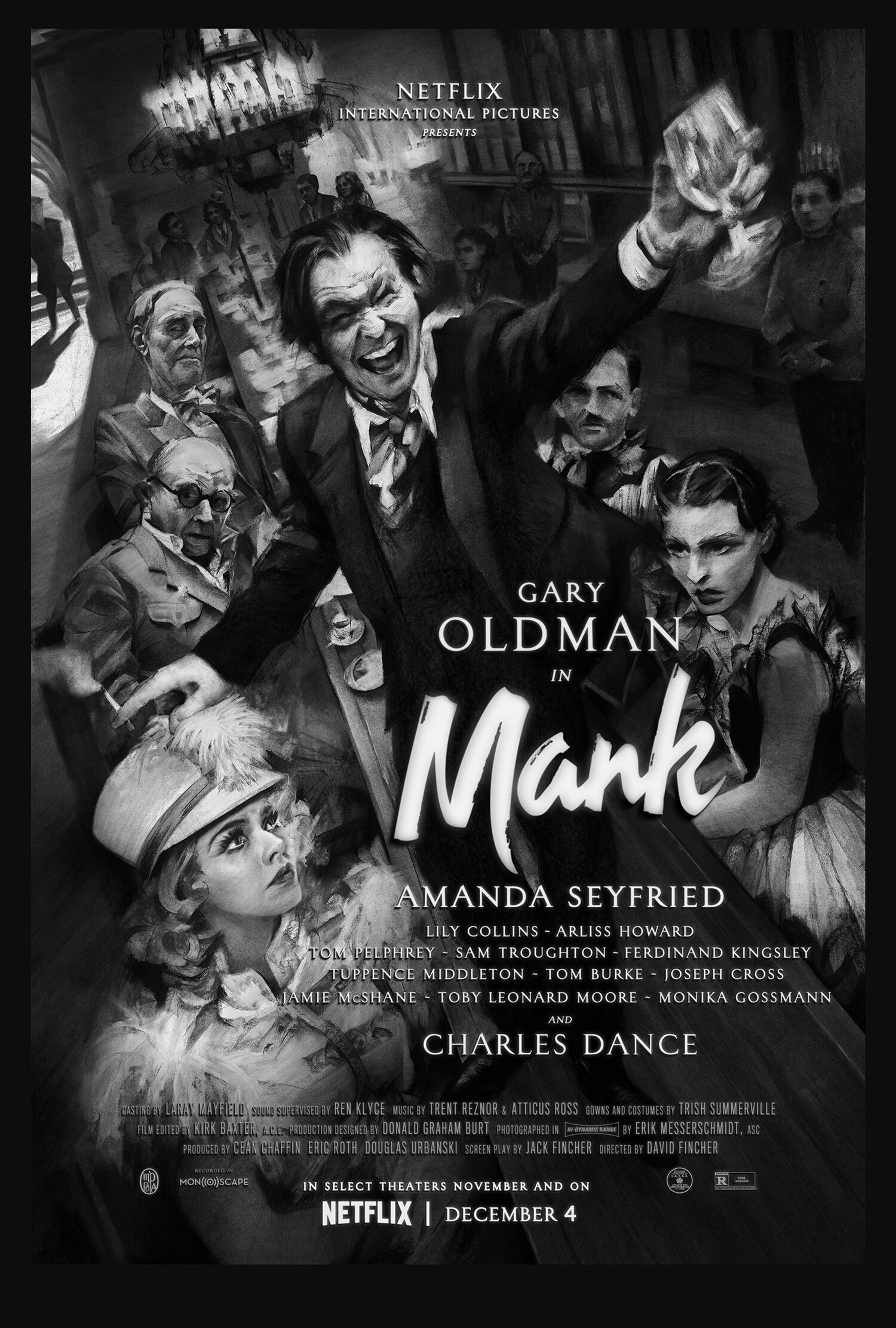

Mank (2020)

dir. David Fincher

Rated: R

image: ©2020 Netflix

“You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression.”

So says Herman J. Mankiewicz early in the biopic about his greatest professional achievement, writing the screenplay for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Mank, that’s precisely what director David Fincher does with Mankiewicz. Here was a man of principle, Fincher shows us. Here was a man of character. Here was a drunk, an inveterate gambler, but above all, here was a man with an absolute conviction in what he believed.

Jack Fincher, David’s father, who wrote the screenplay for Mank before dying of cancer in 2003, structured his own story much like Citizen Kane. The picture loops and swirls from the present of Mank working on Kane in 1940 to the previous decade of his life leading up to that project. The structure is, as Mank says at one point of Kane, “one big circle, like a cinnamon roll.”

Badly needing a paycheck, Mank agrees to pen Welles’s first foray into Hollywood. Welles, the radio wunderkind hot off his successes directing for the stage and with his hugely popular Mercury Theatre on the Air broadcasts, signed a two-picture deal with RKO in which he had complete creative control, including final cut approval.

There is one string attached to Mank’s deal. He will write the screenplay, but, as Welles is also working on his own draft and will produce, direct, and star in the film, Mank will receive no screen credit for his work on Kane. Welles sets Mank up at a house in Victorville, California, away from all distractions – his family stays back east, Welles forbids liquor in the house – under the supervision of producer John Houseman.

Mank must abide by the rules, because he has a broken leg from an automobile accident, making him effectively immobile. He’s wily, though. He smuggles in a prodigious amount of booze with the help of his housekeeper, Fräulein Frieda. In the first hint the movie gives us of our flawed hero’s deeply held principles, Mank’s secretary and stenographer, Rita, discovers why Frieda is so dedicated to her employer. He helped fund her and her family’s escape from Nazi Germany.

Fincher makes his movie walk and talk just like Citizen Kane and other classic films of Hollywood’s Golden Age. He and cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt shot the film in dazzling black-and-white – Fincher initially planned on making Mank after the release of his 1997 film The Game, but his insistence on not shooting in color is the reason the project stalled for 20+ years.

There are little touches that drove this cineaste wild: cigarette burns (for an explanation of what those are, see Fincher’s Fight Club) embedded into the movie every 20 minutes or so; sound design that makes the dialog and music sound like they were recorded on equipment that was used in the Kane era; a magical opening credits sequence with touches like “Netflix International Pictures” and “Filmed in HDR” splashed on the screen. I was surprised that Fincher didn’t shoot in the classical boxy Academy aspect ratio of 1.37:1 (Kane’s ratio), instead opting for a very wide 2.20:1 ratio. It’s the one element that doesn’t quite match what the director is doing with the rest of his movie.

As much as I enjoyed Fincher’s exacting style and homage to old Hollywood in Mank, I remained skeptical of the film’s substance until its second act. Upon reflection, I felt what any critic who gave Citizen Kane a negative review – surely there was one, right? – must have felt, at least until Mank really gets beneath the surface of its subject.

My feelings in the opening twenty or thirty minutes mirrors the reservations the character John Houseman expresses about the first pages of the Citizen Kane screenplay. It jumps around in the life of the main character, making it hard to really get a sense of who this man is. It’s self-consciously showy.

I think the scene that turned me around was the flashback to a birthday party at San Simeon, the lavish estate of William Randolph Hearst. The billionaire newspaper magnate – think Jeff Bezos in terms of wealth and power – is the villain of the film. This elite businessman, who served as the inspiration for Charles Foster Kane in Mankiewicz’s screenplay, takes a liking to the playwright and drama critic who came west to write for the screen. In the early 1930s, Mank befriended actress Marion Davies, the decades-younger mistress of Hearst. She acted as Mank’s entre into the newspaper tycoon’s world.

At the party, MGM studio chief Louis B. Mayer, another central character in the film, talks about the new leader of Germany, Adolph Hitler. Hearst is no fan of the fascist Nazi party, but he has even less tolerance for the socialist movement in his own backyard of California. The writer and leftist political activist Upton Sinclair is running for governor, a candidacy which Hearst eventually demolishes using the weight of his newspaper empire and an ugly smear campaign.

Mankiewicz, himself a leftist and supporter of Sinclair’s policy proposals, follows Davies to console her when she walks out of the party after making unpopular statements, as far as Hearst is concerned, about Hitler and Sinclair. The two connect over a conversation about the cut-throat movie business and politics. It’s the first inkling we get about Mank’s moral compass.

From this point, the flashbacks focus on Mank’s support of Sinclair – who promised real economic power for working people during the Great Depression – and his growing antipathy for Hearst, who enlists one of Mank’s director friends to shoot anti-Sinclair propaganda films.

The friend, Shelly Metcalf, also a Sinclair supporter, takes the job because he desperately needs the money during the depression. The character is fictional, but he’s based on Felix E. Feist, who was a test-shot director at MGM, and did shoot the real-life propaganda films for Hearst. The fictionalization probably comes down to an added emotional punch that comes at the conclusion of Shelly’s subplot.

We see Mankiewicz become increasingly disillusioned with Hearst putting money and power above working people, so it was easy for me to identify with him. I was Mank during the 2016 election, as I saw half of my fellow citizens look the other way from racism, sexism, and hatred because they cared more about their own economic stability. (It would be easy to make the Trump=Hearst comparison, but Hearst was 1000 times the businessman that Trump could ever hope to be.)

The leftist sensibility culminates in an election night party that Hearst throws, and that Mank attends against his better judgement. The movie gives us a tangible feel for why he decided to turn his associate Hearst (the word friend doesn’t quite fit) into the vainglorious, flawed Charles Foster Kane.

Fincher’s film does grasp for the easy dramatic shortcut in one instance. In the film’s final minutes, Mank has decided he wants to fight for screen credit, because Kane is his best work. Orson Welles – actor Tom Burke gives an uncanny performance as the iconic artist – shows up to argue about it. When it’s clear that Mankiewicz won’t back down, Welles flies into a rage, smashing furniture before he storms out. This, of course, gives Mank the final touch he needs for his script, the iconic scene in which Charles Foster Kane does the same thing. It’s a biopic trope that Fincher couldn’t resist.

Gary Oldman is truly brilliant as Mankiewicz. In the climax of the film, in which a heavily drunk Mank shows up uninvited to a costume party Hearst is throwing, Oldman puts on a bravura display of seething anger. He describes the basic outline of Citizen Kane to Hearst, Mayer, and the rest of the party, and he sums up his feelings for Hearst when he uncontrollably vomits on the floor.

Fincher has been called out – rightly so – for casting the 62-year-old actor to play Mankiewicz at ages ranging from 33 to 43. One could make the case that the screenwriter’s heavy drinking made him look much older than he was, but it’s more likely that Hollywood sexism played a part in Oldman’s casting.

Mankiewicz’s wife, Sara, who was the same age as her husband, is played by Tuppence Middleton. The actress is 33, but plays 43 for the bulk of her scenes. Likewise, Marion Davies, who was also the same age as Mankiewicz, is portrayed by 35-year-old actress Amanda Seyfried. It’s a not-so-subtle nod to the entertainment industry idea that men only get better with age, while women are essentially finished once they hit forty. Both Middleton and Seyfried do wonderful work, despite the movie giving them – especially Middleton – woefully little to do.

Character actor Arliss Howard is unrecognizable as L.B. Mayer. Howard gives a striking portrayal of the old-Hollywood producer. His best scene comes in a splendid, sustained tracking shot in which he describes to Mankiewicz and his brother, Joseph, the three things that guide the making of MGM pictures. He points to his head, his heart, and then he squeezes his groin. I have to think that squeeze is an homage to Howard’s best-remembered role as Pvt. Cowboy in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, which also features the same motion in the “this is my rifle, this is my gun” sequence.

David Fincher is a cinematic craftsperson of the highest order who also incorporates great substance into the stories he tells. That tracking shot I mentioned above is but one example of his elegant style. He also evokes the Golden age of Hollywood in Mank with a recurring visual motif. After each major event in the story, the camera returns again and again to an identical close-up of the spiral notebook Mank uses while writing Kane. These artistic touches, and the layered moral dilemma at the heart of Mank, don’t tell the whole of Herman J. Mankiewicz’s life. But they do combine to leave one hell of an impression.

Why it got 4 stars:

- I’m a sucker for movies about movies, in particular movies about movie history, and Fincher gets the style of the period just right. His portrait of Mankiewicz is also layered and incredibly rich. I can’t wait to dive into this one again. I’m certain new layers will be unlocked with each subsequent viewing.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- There’s a great one-scene cameo appearance (lasting all of a minute or so) from Bill Nye as Upton Sinclair.

- One of the best lines of the movie comes from David O. Selznick when Mank and some other writers pitch shooting a horror movie at Paramount: “I don’t make cheap horror films, Universal does.”

- I never even touched on the character of Irving Thalberg. If you aren’t familiar, Thalberg was a boy-wonder movie producer. If you watch the Oscars telecast, you’ll hear his name, when the presenters announce the winner of the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for outstanding achievements in production. The way he’s presented here, he was a go-along-to-get-along kind of guy who gladly sold out his personal beliefs to curry approval from Louis B. Mayer. His relationship with Mankiewicz puts our hero’s convictions in a starker contrast.

- I also didn’t mention Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s phenomenal old-Hollywood tinged score. It’s beautiful and sets the mood perfectly in each scene.

- Most clever word play in the movie: Marion Davies is desperate to be cast as Marie Antoinette in a movie about the French ruler’s life in order to up her dramatic acting bona fides. At one point, Mank drunkenly says to himself: “Marion Antoinette…marionette.”

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- Netflix has released Mank in a limited number of theaters, but to avoid the high risk of COVID infection that movie theaters pose, you can also see it on their service if you have a subscription, which is how I saw it.