The most interesting thing about A Hologram for the King is its title. It isn’t a bad movie, but about the best I can do is damn it with faint praise. It’s just okay. Based on the novel by Dave Eggers, Hologram tells the story of Alan Clay, a down-on-his-luck salesman who travels to Saudi Arabia to pitch a new I.T. and teleconferencing system to the King. Alan’s company spent millions developing this revolutionary new system, which incorporates hologram technology so that corporations and (in this case) governments can hold meetings with people across the globe in a way speaker phones and video monitors could never do. A trip that should take about a week turns into months, however, as Alan and his team are continually rebuffed by the royal officials: they are given a tent with no air conditioning, no food, and no Wi-Fi signal to prepare their presentation. They don’t even know when the King will be in town, much less when he will view their presentation. Along the way, we learn about Alan’s problems, and watch as he makes connections with an eccentric cab driver, a Saudi doctor, and the Danish ambassador to the Middle Eastern country.

A Hologram for the King is so episodic that it just barely hangs together as a narrative. Day after day Alan oversleeps and misses the shuttle from the hotel to the King’s Metropolis of Economy and Trade, where his team is trying to prepare for their presentation. Each time he sleeps through his alarm, Alan calls Yousef, a man the hotel concierge recommends. Yousef isn’t so much a cab driver as he is a guy with a somewhat reliable car who is willing to drive Alan the several hour commute. This is a fish-out-of-water story, and Yousef lies squarely in the territory of the character whose eccentricity belies his ability to lead our hero through this strange new land.

Read more...

From frame one, actor Don Cheadle’s feature film directorial debut pulses with kinetic energy and excitement that doesn’t break until the last credit rolls. Miles Ahead covers a few hectic days in the life of jazz icon Miles Davis and Cheadle does triple duty co-writing, directing, and starring. There are three major pitfalls that movies in the biopic genre often find hard to avoid: 1) trying to cover so much of its subject’s life that the movie becomes unfocused; 2) creating a glowing portrait of the subject that erases any real-life hard edges; and 3) following a standard formula of rising to fame/power from humble beginnings, a tragic fall from grace, and finally redemption. Movies detailing the life of an artist or musician find it particularly hard to avoid that last one. Walk the Line and Ray come instantly to mind. Miles Ahead deftly sidesteps all three. This is the un-biopic biopic, and it’s every bit as passionate and bold as the music of the man whose story it tells.

Read more...

There is a moral ambiguity to Eye in the Sky that acts wonderfully as a test for each person watching it. Depending on your feelings about the importance of maintaining a moral high ground relative to your enemy, it’s possible to have a very different experience with the film than the person sitting right next to you. Even if you agree with that person on how the so-called “war on terror” is prosecuted, it’s easy to read the message the movie is sending in a wildly different way. That is Eye in the Sky’s most powerful strength. It deftly presents opposing sides to the ongoing debate of the best way to stop terrorists, then forces you to think critically about the issue and pick a side. Dramatically speaking, the film is also an incredibly taut thriller; it’s expertly paced for maximum tension. The picture achieves this by taking the overused “ticking time bomb scenario” and adding an element that complicates what is usually presented as an easy call by films and television shows of this nature.

Read more...

Midnight Special is many things. It’s a moody science fiction throw back in the vein of E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It’s an intense on-the-run movie which takes place over the space of a few frantic days. It shows the destructive force of religious cults, and the extreme measures true believers will go to in the name of their convictions. Ultimately, Midnight Special is a tightly wound tale of a father and mother who will do anything for their child, who is at the heart of it all.

Director Jeff Nichols’ first two films, Shotgun Stories and Take Shelter, are both meditations on American families in the process of breaking down. In the former, years of uneasy pressure between two sets of half-brothers in Arkansas come to a boil when the patriarch of the two clans suddenly dies. The latter examines a man in Ohio whose family must face the consequences of his slow descent into mental illness. So it’s no surprise that family is at the core of Nichols’ fourth and latest film, as well.

Read more...

Last week I wrote about Richard Linklater’s film Everybody Wants Some, his “spiritual sequel” to Dazed and Confused. 10 Cloverfield Lane could very easily be described similarly alongside its 2007 predecessor, the found footage monster movie Cloverfield. But producer J.J. Abrams has instead taken to calling the film a “blood relative” of the original, which he also produced. Think of the two Cloverfields as feature length, big budget anthology entries in a show like The Twilight Zone, or The Outer Limits. Their connective tissue is a sci-fi milieu, and a rich atmosphere that envelops you in dread.

The film’s official synopsis is, “Monsters come in many forms.” That is a supremely superb and succinct sketch – an excellent example of the Shakespearean proverb, “Brevity is the soul of wit.” The set up to the film, directed by Dan Trachtenberg, is equally simple. A young woman named Michelle survives a car crash and wakes up in her rescuer’s underground fallout shelter. The man, named Howard, tells Michelle that some invading force has poisoned the air, and that it’s not safe to go above ground for a year or two. Michelle and Howard aren’t alone, though. An acquaintance of Howard, a young man named Emmett, saw that the older man was acting strange, and convinced Howard to let him into the shelter before sealing it.

The next hour and a half plays out as an incredibly tense chamber drama. 10 Cloverfield Lane is a masterclass in paranoia filmmaking. Even though Emmett believes everything Howard says about the danger above ground – the older man claims he saw atomic-like blasts – Emmett didn’t actually witness anything himself. Complicating matters, Howard proves to be unstable at best, kind and fatherly but capable of exploding into bouts of rage when contradicted. So, Michelle isn’t sure who to trust or what to believe. In addition to Howard’s erratic behavior, Michelle can’t be totally sure he didn’t run her off the road in the first place. She also awoke in the concrete bunker with her leg chained to the wall. That early scene is evocative of a movie like Saw, and it succeeds in producing the uneasy feeling that at any moment the movie could shift into torture porn.

Read more...

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot is a dramedy that isn’t funny enough to make it memorable as a comedy, and it isn’t moving enough to make it memorable as a drama. It’s muddled, not really sure what it wants to be. The movie suffers immensely from this lack of commitment. It also actively refuses to take any meaningful stance on the issues central to its plot – journalists covering the American invasion of Afghanistan – leaving the picture like a news story that fails to inform or entertain.

The story revolves around real life American journalist Kim Baker and her adventures while covering the war in Afghanistan. Whiskey Tango Foxtrot (the military phonetic alphabet translation of the letters WTF, so the title is a joke on the popular shortened version of the expression “What the fuck?”) is based on Baker’s memoir, The Taliban Shuffle: Strange Days in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Shepherded through the book-to-screen process by star Tina Fey’s production company Little Stranger, the movie transforms its war-torn backdrop into a self-discovery tale with a splash of romantic comedy. It’s an unlikely setting for such a story, one the filmmakers would have been wise to avoid.

There is a scene in the middle of WTF when an Afghan woman asks Baker what made her decide to travel half way around the world to cover the war. Fey, as Baker, sums up her need to escape her life using the exercise bike at her gym to illustrate her point. Baker tells the woman that one day she noticed an indentation in the carpet just in front of her regular stationery bike. She realized it was where the bike used to sit before a gym employee moved it for one reason or another. In that moment, Baker says, she understood she had spent countless hours on that bike, only to move backward three feet. “Wow,” her interlocutor observes, “that’s the most American white lady story I’ve ever heard.”

It’s a funny moment to be sure, and it’s a sly attempt at winking at the audience. We know exactly what kind of story we’re telling, the movie says, and our effort at being up front about it will hopefully earn us some points with you, the audience. It doesn’t, though, because despite this self-awareness by the filmmakers, the rest of the movie is as predictable as you would expect. WTF is Eat, Pray, Love goes to war, and that’s just as disappointing of an exercise as you might expect.

Read more...

My initial reaction to Charlie Kaufman’s new film, Anomalisa, was to call it his most solipsistic work yet. The central character, Michael, is a famous self-help author who has a little problem with the way he relates to other people. While watching the film, I interpreted his problem (I don’t want to spoil this central plot point of the movie, so I’ll try to dance around it) as a way for Kaufman to explore one man’s narcissism. His rather unique inability to connect with those around him seemed like a study in self-absorption. Then I did some homework on the movie.

The screenplay is an adaptation from Kaufman’s own 2005 play, written for a unique artistic endeavor called “Theater of the New Ear.” It was a series created by musician and film composer Carter Burwell, and it was an attempt to bring to life the old live action radio plays of the 1930s and 1940s. The actors were seated at desks on stage, reading their lines while a live orchestra and foley artist created the music and sound effects. When I came across the pseudonym Kaufman used for his play, Francis Fregoli, everything clicked into place. Solipsism and narcissism aren’t what Kaufman is really interested in here, after all. I’ll let you decide if you want to Google Fregoli Syndrome before seeing Anomalisa, but I don’t think knowing the secret would irreparably spoil the movie. Rest assured, he uses the device to explore his trademark preoccupations: existential dread, personal isolation, and general unease with society at large. As is the case with every other work Kaufman has crafted, there are many layers to Anomalisa. It’s a difficult, thought provoking picture, and one that you’ll wrestle with long after you’ve seen it.

Read more...

It’s been well documented, especially with the advent of the Twitter hash tag #OscarsSoWhite, that the make-up of the Academy is overwhelmingly old and glowingly white. Oscar voters love to reward films that treat the not-too-distant past with a loving soft focus. For every 12 Years A Slave that demands a reckoning with ugly truths, there is a Driving Miss Daisy that reaffirms things weren’t all that bad, really. Brooklyn is one of those. Set in 1952, the movie focuses on one of the many Irish citizens that came to America at the time. There’s a long history of Irish immigrants being looked down on by people who considered themselves “real Americans,” but the movie dispenses with this mentality by using it for a quick bit of comic relief. The main character Eilis (in the character’s home country of Ireland, it’s pronounced AY-lish) learns that all it takes to assimilate to the American way of life is grit and determination. Because this is a movie devoted to a rose-colored view of history, that’s all Eilis needs in order to succeed.

There is a sentimentality and nostalgia for a simpler time that permeates every frame of Brooklyn. As you might expect from a movie that completely romanticizes a bygone era, the filmmakers take great care in beautifully photographing their tale. The performances from the leads, too, are top notch. Those elements can’t overcome the simplistic and predictable story, though, or the movie’s slavish devotion to its idea of the good old days.

Brooklyn tells the story of Eilis Lacey, a young Irish girl who moves to the New York borough in search of a better life. Eilis experiences seasickness while aboard the steamship that transports her to America and, in an example of the easily digestible kind of symbolism Brooklyn employs, the suffering she endures on her first trans-Atlantic trip represents the crushing homesickness she struggles with while trying to adjust to life in a new world. During the journey, a more experienced traveler takes Eilis under her wing. The woman provides instruction on what food to avoid while on board and, more importantly, how to conduct herself once they arrive at the U.S. port of entry.

Read more...

Director Lenny Abrahamson’s film Room is an incredibly intimate study of the resiliency of the human psyche. The movie – based on author Emma Donoghue’s award winning 2010 novel of the same name – is bleak and tragic while being simultaneously hopeful and life affirming. It’s also an intense character study that churns the stomach with suspense, all without feeling exploitative. The craftsmanship of the movie on a technical level, from the beautiful cinematography to the heart-breaking performances, is of the highest quality.

Room tells the story of Joy and her five-year-old son, Jack. Joy was abducted as a teenager by a man she and Jack call Old Nick, who holds them in a shed about the size of a prison cell they both refer to simply as “Room.” Joy hasn’t been outside Room in seven years, and it’s all Jack has ever known. Old Nick routinely rapes Joy, and Jack is the product of one of those assaults. The story is fiction, but author Donoghue was inspired to write it after hearing the horrific true life details of survivor Elisabeth Fritzl, whose story is also disturbingly similar to those of the three young women recently kidnapped and imprisoned by Ariel Castro. Room details Joy’s attempt to get Jack out, and the aftermath of her plan.

It’s a real surprise that one of the most engaging and uplifting movies to come out of 2015 is centered around the creation of a mop. Joy is a film by writer/director David O. Russell, though, so there is much more swirling around that main plot point. Within the semi-autobiographical story of Joy Mangano – the entrepreneur responsible for the Miracle Mop – are the ups-and-downs of a real life Horatio Alger story, a nostalgic look back at the novelty of the QVC shopping channel, and a family drama reminiscent of a John Cassavetes film like A Woman Under the Influence.

Russell has had two major preoccupations in his filmmaking career. One is historical period pieces focusing on fictionalized events of true stories in the very near past, reflected by his films Three Kings and American Hustle. The director’s other mode is his intense examination of family dynamics, and the more dysfunctional, the better. That subject is represented by films like Spanking the Monkey, Flirting with Disaster and Silver Linings Playbook. Joy, like his 2010 film The Fighter, is a melding of the two.

Set in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Russell frames his story of a woman struggling with the idea that she’s meant for greater things through the lens of a soap opera, an obsession of the main character’s mother. We’re clued into this with the movie’s introduction, an overwrought scene from the mother’s favorite soap that Russell stages with cheesy, histrionic glee. It serves as a key to the rest of the movie. Joy Mangano may be a real person, but just like soap operas are a melodramatic version of reality, the movie Joy is a fusion of real life and amplified drama.

Read more...

Does the revelation that the American financial system is a complete fraud, a rigged game, go down smoother if the message is delivered in the form of a zany mockumentary-style comedy? Director Adam McKay thinks so. The Saturday Night Live alum, whose film work includes outlandish comedies like Anchorman, Talladega Nights, and Step Brothers, brings his trademark screwball style to the inside story of the economic crash of 2008. While the wacky comedy is firmly in place, The Big Short is also a departure for McKay, dealing with some very serious themes like what happens to the rest of us when members of the elite financial system decide to treat the economy like it's a casino. McKay’s sensibilities are a little too over the top for the story he wants to tell, but the director shows great promise at blending comedy and drama.

There’s an obvious comparison to be made to Martin Scorsese’s 2013 film The Wolf of Wall Street. That film dealt with an unscrupulous financial wizard who broke all the rules to make himself a millionaire, and it also uses hyper stylized action and outlandish comedy to tell its story. The reason Wolf works better than The Big Short is because each movie’s goal is different. The Wolf of Wall Street isn’t overly concerned with making the audience understand how Jordan Belfort went about gaming the system. It’s simply a tale of his excesses. The amped up, jittery aesthetic works splendidly to telegraph those excesses. In The Big Short, McKay wants to inform his audience about what went wrong, and he wants us to become angry at the lack of accountability in the aftermath of the crash. The fidgety style McKay employs, while wildly entertaining, distracts from his goals.

Read more...

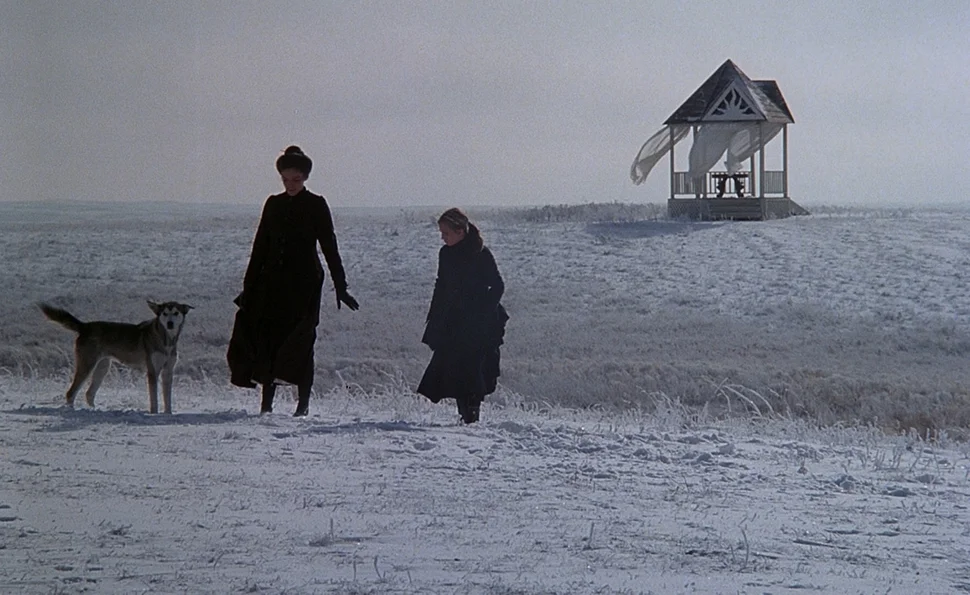

As if we needed any more confirmation, director Quentin Tarantino has proven again that he is a singular talent. There’s a real irony in what makes his films unique, because his art depends so heavily on referencing other movies. The man is like a cinematic blender; he fills himself with his favorite genres, and he violently liquefies them all into a wholly new product. The product this time is The Hateful Eight, a western that mines such distinct storytelling approaches as both an Agatha Christie drawing room murder mystery and John Carpenter’s The Thing, with more gallons of blood than Brian de Palma’s Carrie.

As big and loud and nauseating and hilarious as the movie is, it’s essentially a small chamber piece with a handful of characters talking to – and sometimes merely at – each other in a room for almost three hours. It could easily (and fascinatingly) be staged as a play. In fact, Tarantino first produced it as a staged reading with cast members like Michael Madsen and Bruce Dern already on board. It’s Glengarry Glen Ross by way of a grindhouse double feature. This eighth film by Tarantino is a blood soaked yarn that is by turns thrilling, disturbing, and troubling, but it further cements the director as a visual stylist and screenwriter who is unrivaled at his craft. The director’s attention to detail, and his loving devotion to the films of the past, is evident from frame one of The Hateful Eight, with an opening shot – filmed in beautiful 70mm Panavision – that is an incredibly slow pan of a gorgeous snow swept landscape.

Westerns are getting the treatment in this movie that he gave to exploitation movies in Grindhouse. If his last film, 2012’s Django Unchained, was an homage to the askew sensibilities of the Spaghetti Western, The Hateful Eight is honoring the classical Hollywood version of the same genre. This is The Alamo if it had been co-directed by Sam Peckinpah and Lucio Fulci. The “roadshow” cut of the film, which is the version I was able to see, even begins with a musical overture in the style of that Western classic. Supplying the overture and the rest of the score is legendary composer Ennio Morricone, whose music is deeply haunting and rich with atmosphere. The man who scored classics like Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy and Once Upon a Time in the West a half-century ago has only gotten better, if that’s even possible. Morricone didn’t have time to provide an entire score, so he gave Tarantino permission to license unused tracks that he previously wrote for John Carpenter’s aforementioned The Thing.

Read more...

I feel it in my fingers, I feel it in my toes… when the month of December rolls around, the need to watch Love Actually is a feeling that grows. I’ve watched the movie at least a dozen times since friends introduced it to me seven or eight years ago. It delivers on that harmless popcorn flick level that never disappoints regardless of how many times you watch it. It’s endlessly quotable, and never fails to get laughs in all the right spots, despite year after year of viewing.

The first scene of the movie, when washed-up rock star Billy Mack attempts a comeback with a yule-themed reworking of The Trogg’s 60s hit Love is All Around, never fails to bring a smile to my face. Most of that joy is created by actor Bill Nighy’s gleefully mischievous performance as Mack. Nighy sinks his teeth into the persona of the has-been rock god like he’s biting into a thick medium-rare steak. I have to wonder if he didn’t serve as an example to the rest of the cast. Everyone involved in Love Actually takes the material they’re given – which is by turns cheesy, silly, funny, and depressing – and together they deliver an unabashedly heartfelt piece of entertainment that doesn’t have a cynical bone in its body. When the film leaves Nighy as he hilariously struggles to shoehorn the correct Christmas references into the song, composer Craig Armstrong transforms the melody into a sweeping orchestral piece as we meet the rest of the characters. The joy of that opening montage is infectious, and if you let it work its magic, you realize that love actually is all around.

Director Richard Curtis set out to make the definitive romantic comedy, so he wrote this tale of nine intersecting stories about the trials and tribulations of love set in the month leading up to Christmas. Based on how many knock-offs have come in the dozen years since Love Actually was released, it’s obvious quite a few screenwriters thought Curtis was on to something. From Valentine’s Day to New Year’s Eve to He’s Just Not that Into You, the formula has been copied, but not as successfully as in Love Actually. Most of that success is thanks to the cast taking Curtis’ over the top situations and creating unforgettable moments with their performances.

Read more...

The story is simple, if unconventional. It’s the early 1900s. Two down-on-their-luck lovers, Bill and Abby, and Bill’s kid sister, Linda, leave the industrial nightmare of Chicago and find work on a farm in the Texas panhandle. The rich, ailing farm owner falls for Abby, and wants to marry her. Bill and Abby decide to cash in, since the farmer probably won’t live much longer. It’s not like the two lovers will need to stop seeing each other, since they hide their relationship from everyone they meet by telling people they are brother and sister.

From that synopsis you might assume Days of Heaven is a standard tale of love, deception, and betrayal. With director Terrence Malick at the helm (who made the even more experimental The Tree of Life), standard never enters the equation. From that basic plot, Malick assembles a quiet meditation on the infinite beauty of the nature that surrounds humanity, and our determination to ignore it in pursuit of material gain. The virtuoso photography of cinematographers Nestor Almendros and Haskell Wexler, and Malick’s lyrical structure combine to make Days of Heaven a superlative example of the 1970s New Hollywood movement.

It’s hard to overstate just how stunning the cinematography for Days of Heaven is. The film won that award at the 1979 Oscars, and because Almendros was listed as principle photographer – Wexler came on when Almendros had to leave to shoot another film – he was the only one to receive the award. Because of the slight, Wexler famously wrote a letter to Roger Ebert in which he described sitting in a theater timing all his footage with a stop watch, proving he was responsible for more than half the picture. It’s easy to see why Wexler was so passionate about it. Practically any frame in the movie could be transferred to a canvas and hung in a gallery, but one shot is particularly breathtaking. It only lasts about ten seconds, but the image of an impossibly huge thunderstorm sweeping across the landscape will give you pause. On the left of the frame is a relatively tranquil, blue sky while the right side of the composition is dominated by the angry tempest invading like a marauding army. Much of the film was photographed at “magic hour,” those fleeting moments at dawn and dusk when the sun paints the sky with beautiful pink and purple hues. The skill of both men to catch those gorgeous colors on film with just the right stock and filters is awe-inspiring.

Read more...

When the credits suddenly rolled at the end of Dangerous Men, my response was to yell “Yes! YES!” at the top of my lungs. No one else in the theater noticed, they were all too busy having their own ecstatic reactions, laughing and applauding in equal measure. Simply put, Dangerous Men is one of the most indecipherable, comically bad movies ever committed to celluloid.

The movie’s plot – what little there is – concerns a woman, Mira, and her fiancé being attacked on a beach by two bikers. The fiancé is killed, and the bikers plan to rape Mira. She cunningly escapes being violated and goes on a mission to get revenge on every man with nefarious intentions she comes across. To describe what happens next as “incomprehensible” is like suggesting that reading The Canterbury Tales in Chaucer’s original Middle English is a bit tough to get through.

There’s no story in Dangerous Men, so much as there are several story threads that are tenuously tied at best. The movie cuts between each one at break-neck speed until the final scene ends in the most abrupt way possible: freeze-framing on three characters we’ve only just been introduced to. It’s as if the idea of dramatic resolution was a physical entity that committed such a heinous crime against the filmmaker, he had no choice but to get his revenge with a bad enough ending that storytelling itself would be mortally wounded.

The auteur responsible for Dangerous Men, Iranian born architect John S. Rad, spent 26 years making his movie, and ultimately self-financed its initial disastrous theatrical run. Rad – born Jahangir Yeganehrad – began filming his trash opus in the early ‘80s, giving the whole film its grungy neon aesthetic. He refused to be buried in debt, so filming became a start-and-stop endeavor, depending on when he had the cash on hand to afford it. Rad completed filming in the mid-90s, and he had to pay out-of-pocket to get the finished product into a few L.A. theaters in 2005. The filmmaker died of a heart attack in 2007, just a few years after Dangerous Men started earning a reputation on the cult, so-bad-it’s-good midnight movie circuit.

Read more...

“What exactly does it mean to be an asshole?”

That was how New York magazine writer Mark Harris boiled down Aaron Sorkin’s screenplay for The Social Network in a 2010 piece on the movie and its screenwriter. Sorkin’s past work is littered with characters that are intensely driven, successful, and can charitably be described as “difficult.” In writing for TV – most notably NBC’s The West Wing – Sorkin knew how to soften the edges of these overachievers. Yes, they could be hard to deal with, but they realized it (usually by the end of the episode), and cared enough about those around them to make amends for their behavior.

Then along came The Social Network, and Mark Zuckerberg. While ostensibly about the creation of Facebook, the movie is actually an intense character study of the website’s founder. Sorkin’s Zuckerberg was an asshole who knew it, but only cared enough to feel a little bad about it – making amends was not that character’s style. After another stint on TV with the similarly fractious Will McAvoy of The Newsroom, now Sorkin gives us Steve Jobs. From Zuckerberg to McAvoy to Jobs, something of an asshole evolution is evident. This time the asshole genius knows what he is and he doesn’t give a damn. The result of Sorkin’s writing is as compelling and multi-layered a character study as he delivered with The Social Network, with a dramatic structure as tight as Citizen Kane.

Read more...

Bridge of Spies is a tale of two films. The second half of Steven Spielberg’s newest historical drama is a good representation of the high level of quality associated with the director’s work. The finale is dramatically tense and emotionally powerful while remaining understated in the message it conveys. The first half stands in stark contrast to all of that; it’s hindered by its rote execution and the way it delivers moral lessons as subtly as an atomic bomb. Bridge of Spies could be leaner and more effective if Spielberg and screenwriters Matt Charman and the Coen brothers had concentrated solely on the second dramatic arc of the story. As it is, the film gives the overall impression of being unfocused.

The movie begins in 1957 as the FBI arrests Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance) on suspicion of being a Soviet spy. The evidence against Abel is quite damning, but the U.S. government wants to show the world that everyone, even those accused of espionage, is afforded the same protections under the law. This protection boils down to having access to competent legal counsel. To that end, the FBI convinces James Donovan (Tom Hanks) – an insurance settlement lawyer with criminal trial experience – to represent Abel. Donovan believes in the American justice system, so he provides his client with a zealous defense, even moving forward with an appeal when Abel is convicted on all counts. He does this to the chagrin of his colleagues at the firm, the judge in the case, and even his own family.

It would be one thing if the writers stuck to the maxim of “show, don’t tell” to illustrate the moral superiority of treating even the worst criminals with the same dignity and humanity granted all U.S. citizens. After all, the case can be made that it’s a lesson worth re-learning since the war on terror began – especially for those in positions of power. But Charman, Spielberg and the Coens don’t just show. They tell, and tell, and tell. Tom Hanks is one of the finest actors of his generation, and his performance in Bridge of Spies is as good as you would expect. But by the fifth or sixth time he explains the importance of due process to those who want blood, the point becomes excruciatingly belabored.

Read more...

If the Oscars nominate Sicario for a best picture award next January, it will be one more example against the argument that “Hollywood” is nothing but a bunch of looney liberals who promote a far leftist agenda. A few handicappers currently have it as a top tier contender. The film is about the U.S. government’s escalating tactics to stop narcotics from crossing the border between Mexico and the States. It is Zero Dark Thirty for the war on drugs, playing like Dick Cheney’s wet dream. The movie is a perfect representation of how neocons like Cheney and his ilk envision prosecuting not only the war on terror, but all wars. They alone get to decide what the rules of engagement are. Sicario is a reactionary, far-right fantasy that’s all the more depressing because it’s probably not that different from reality.

The film begins with FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) en route to raid a house in Arizona where a Mexican drug cartel is suspected of holding kidnap victims. When the raid is over, Macer and her SWAT team make a gruesome discovery: the cartel hid dozens of bodies inside the walls. The situation gets even worse when several FBI team members are killed by an improvised explosive device rigged in a backyard shed. Macer’s boss introduces her to Matt Graver (Josh Brolin), a mysterious figure who is leading a new task force. The explosion and deaths in Arizona have changed the game, Graver explains, and they need to take the fight to the cartels. He wants Macer to join his team, but she has to volunteer. She does, with the stipulation that she can bring her partner Reggie (Daniel Kaluuya) along. Their convictions are soon put to the test. Witnessing blatant disregard for the rule of law and an invasion of sovereign territory, Macer eventually suspects the use of torture, as well. All in the name of fighting the war on drugs.

Read more...

Holly Martins has the worst luck. The broke writer travels to Vienna shortly after the end of World War II because his best friend, Harry Lime, offers him a job. Within the opening minutes of director Carol Reed’s classic noir thriller The Third Man, Martins walks under a ladder – a harbinger of bad luck – and soon learns that a car struck and killed Lime a few days earlier. Martins is now adrift in a foreign land with no money and no prospects, but things are about to get much worse. Major Calloway, a British officer who is part of the post-war occupying force in Vienna, tells Martins that his childhood friend was a criminal, a profiteer within the city’s thriving black market. Martins decides to clear his friend’s good name and, as a result, he’s pulled into intrigue that challenges his belief in the decency of humanity. Along the way he meets Anna, Lime’s lover, who is ferociously loyal and is devastated by his death.

Because we’re travelling through noir country in The Third Man, the worldview is bleak, practically nihilistic. Made in 1949, the film explores the existential crisis experienced after the most deadly war in history ended. Life is cheap, take all you can while you can, and don’t look out for anybody but yourself.

Read more...

The question with biopics is always what should be included, and what’s reasonable to leave out. Depicting the events of even a few years of a person’s life is incredibly hard to do. The filmmakers have to hone in on a very carefully selected handful of events that will convey to the audience the essence of the people and times the film covers. By that standard, Straight Outta Compton is a frustrating disappointment. It’s frustrating because the shortcomings of the narrative detract from what is otherwise a powerful piece of filmmaking.

Stylish and gritty, Straight Outta Compton will surely become the definitive visual history of the musical revolution set off by artists Easy-E, Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, DJ Yella, and MC Ren. Director F. Gary Gray, with the help of cinematographer Matthew Libatique, created a film that’s gorgeous to look at, and has been praised by people who experienced the time and place the film covers – such as Selma director Ava DuVernay in a tweet storm about her reaction to the movie.

The problem with the film is that the winners, specifically Dr. Dre, got to write their own history. Dre was among the producers for the film, and his character is written as undeniably heroic. He’s a flawed hero, to be sure, but he’s a hero who stands up to violence and those who perpetrate it. Unfortunately for him, we live in a time when the people stepped on by the winners can still have their say. As a result, Straight Outta Compton rings hollower than it otherwise would.

Read more...