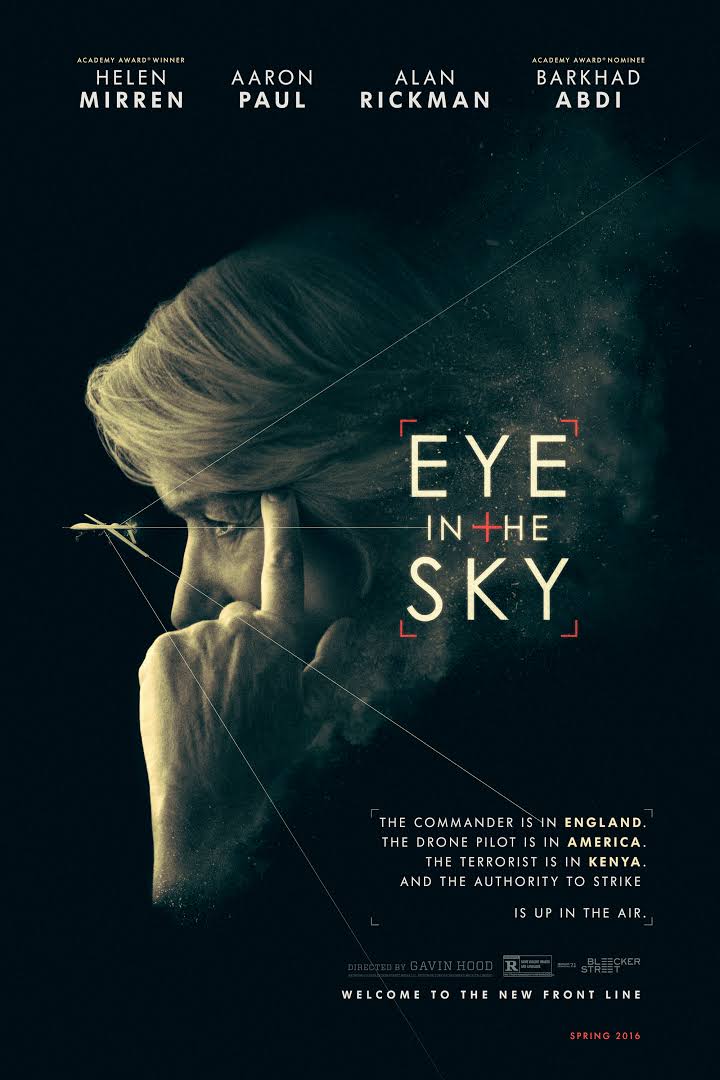

Eye in the Sky (2015)

dir. Gavin Hood

Rated: R

image: ©2015 Entertainment One

There is a moral ambiguity to Eye in the Sky that acts wonderfully as a test for each person watching it. Depending on your feelings about the importance of maintaining a moral high ground relative to your enemy, it’s possible to have a very different experience with the film than the person sitting right next to you. Even if you agree with that person on how the so-called “war on terror” is prosecuted, it’s easy to read the message the movie is sending in a wildly different way. That is Eye in the Sky’s most powerful strength. It deftly presents opposing sides to the ongoing debate of the best way to stop terrorists, then forces you to think critically about the issue and pick a side. Dramatically speaking, the film is also an incredibly taut thriller; it’s expertly paced for maximum tension. The picture achieves this by taking the overused “ticking time bomb scenario” and adding an element that complicates what is usually presented as an easy call by films and television shows of this nature.

Presented in near real-time, Eye in the Sky follows the myriad personnel involved in a multinational effort to capture two high-level terrorists. At the head of a six-year search for these terror suspects is British military intelligence officer Colonel Katherine Powell. Played with a steely conviction by Helen Mirren, Colonel Powell is desperate to take into custody the two Al-Shabaab extremists that she’s been relentlessly hunting for so long. She finally gets her chance when the pair turn up at a safe house in Nairobi, Kenya. In the first complication of the plot, the audience learns that one of the two is a British national. Because of due process concerns, law dictates that this woman must be taken into custody instead of being executed without a trial.

British intelligence sets the capture mission in motion, with military from, and governmental agencies on, three different continents working in tandem. While Powell leads the effort from International Command Headquarters, Lieutenant General Frank Benson supervises the operation from London, with several members of the British government present as both witnesses and the necessary authority. At a base in Nevada, American USAF pilots Steve Watts and Carrie Gershon strap in to act as the mission’s titular eye in the sky, remotely operating a drone equipped with two Hellfire missiles. Finally, undercover Kenyan field agents, including Jama Farah, assist on the ground with surveillance equipment and the objective to take the suspects into custody at the right moment.

Things don’t go as planned, however, when the extremists leave the first location after only a few minutes and drive to an area of Nairobi that is controlled by Al-Shabab. Farah must infiltrate this highly dangerous area in order to get a video feed of what is happening inside the new location to Colonel Powell. Everyone’s worst fears are realized when Farah’s surveillance feed shows a huge cache of explosives being loaded into two suicide vests which could be used at any moment.

This is the set-up of the ticking time bomb scenario I mentioned before. As any fan of the television show 24 can attest, this plot device has been used countless times in film and television. It can justify any number of unsavory tactics in order to get information out of suspects or to kill suspected terrorists without the pesky nuisance of a trial. Former Vice President Dick Cheney and other high ranking officials in the Bush administration routinely evoked both the specter of the ticking time bomb scenario and the greatest purveyor of the trope itself, 24, when justifying the use of torture as American policy. The way Eye in the Sky subverts this trope is to add a second ticking time bomb, if you will. Only this one is in the control of the British and American governments.

Early in the film, we are shown a Kenyan couple with a young daughter, Alia, likely 9 or 10 years old. The girl loves playing with the homemade hula hoop her father has made for her. Every morning the girl’s mother sends Alia to a bustling city street to sell bread the family bakes as a way to supplement the father’s income as a local handyman. Her chosen spot to set up shop is right outside the house where the suicide vests are being prepared.

Because of the potential loss of life from the suicide vests, and frankly because of her obsession with taking out the extremists she’s been chasing, Colonel Powell is determined to change the mission from capture to kill. She wants the American drone pilots to use the Hellfire missiles on board their craft to incinerate the safe house and all those inside it. The members of British government watching events unfold from London are hesitant, however, because the little girl selling bread will most assuredly be killed in the strike.

And so, little Alia becomes a potential representation of every innocent person killed in the wake of drone strikes launched with the purpose of killing high-value terrorists. Much of the drama of the film, and the intellectual debate of what kind of killing is justified in the name of peace, comes out of the danger this little girl is in. At one point, Jama even attempts to buy all of Alia’s bread, so she will leave. He is recognized by one of the neighborhood Al-Shabab members, and this leads to a tense subplot where Jama runs for his own life.

Since the missiles are American property, British government officials desperately try to contact the U.S. Secretary of State, who is on a diplomatic trip to China, in order to get an okay from him. Meanwhile, the jihadists who will wear the suicide vests are making their final video propaganda statements. The political wrangling of who needs to approve what when multiple nations are involved in such an operation speaks to the pass-the-buck mentality these kinds of situations breed.

There are weaknesses that aren’t easy to overlook in Eye in the Sky. The surveillance equipment Jama uses, like a tiny flying camera made to look like an insect, to get the video of the explosives in the first place, strains credulity. It screams movie magic. Some of the choices writer Guy Hibbert makes to put the moral implications of the story in such stark relief could be attacked as ham-fisted. At one point a customer of Alia’s father sees the girl playing with her hula hoop. He is very disturbed that a girl would be moving in such an unchaste way, and he lets the father know about it. After the customer leaves, Alia is told that they are not like everyone around them, who are all religious extremists. Her father tells her she must be careful, and only play in front of her family. It’s not a very subtle moment, but neither is using a 10-year-old girl’s possible death to make a point about drone warfare.

What makes up for these shortcomings is Gavin Hood’s masterful direction. The anxiety produced by the major question of the film, will the strike go ahead or not, is palpable. Hood does a superb job with the action sequences in the film, especially considering many of them revolve around people sitting in front of video screens watching events play out thousands of miles away.

Eye in the Sky presents arguments both for and against going ahead with the strike. Isn’t it worth the collateral damage, which will undoubtedly be much less than the number of innocent people killed should the suicide vests be used as planned? What is the risk of creating more terrorists if the families of innocent people who are killed turn against the Western nations responsible for unleashing hell from the sky via remote controlled warplanes? How you react to these kinds of moral questions is what makes Eye in the Sky such a thought provoking movie. It doesn’t provide its audience with easy answers, and that makes it a richer experience than it otherwise would be.

Why it got 3.5 stars:

- I walked away from seeing the movie saying it was one of the best of the year, but I've cooled towards it since. Much of my initial high estimation came from what an intense experience Eye in the Sky is. After reflecting on it for a while, the problems (the heavy-handedness of the plot, the unbelievable spy-craft tools) stood out more in my mind.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- There is so much plot description needed, and the themes arising from that plot were so interesting to me that I basically didn't mention the cast of the film, which is stellar. Besides Helen Mirren (who does a fine job walking the line between being sympathetic as a soldier who has spent many years in pursuit of terrorists and provoking disdain because of what she's willing to do to end that pursuit) excellent performances are turned in by Aaron Paul, Phoebe Fox, Barkhad Abdi, and the late, great Alan Rickman. Paul, in particular, gives a heartbreaking performance as the Air Force pilot who will be responsible for firing the missile that will kill dozens, should it come to that.