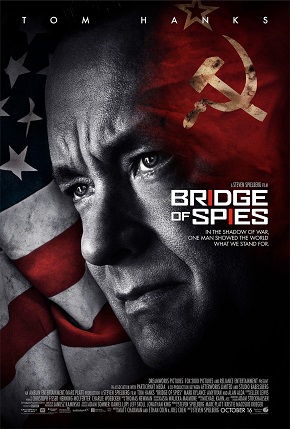

Bridge of Spies (2015)

dir. Steven Spielberg

Rated: PG-13

image: ©2015 Disney

Bridge of Spies is a tale of two films. The second half of Steven Spielberg’s newest historical drama is a good representation of the high level of quality associated with the director’s work. The finale is dramatically tense and emotionally powerful while remaining understated in the message it conveys. The first half stands in stark contrast to all of that; it’s hindered by its rote execution and the way it delivers moral lessons as subtly as an atomic bomb. Bridge of Spies could be leaner and more effective if Spielberg and screenwriters Matt Charman and the Coen brothers had concentrated solely on the second dramatic arc of the story. As it is, the film gives the overall impression of being unfocused.

The movie begins in 1957 as the FBI arrests Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance) on suspicion of being a Soviet spy. The evidence against Abel is quite damning, but the U.S. government wants to show the world that everyone, even those accused of espionage, is afforded the same protections under the law. This protection boils down to having access to competent legal counsel. To that end, the FBI convinces James Donovan (Tom Hanks) – an insurance settlement lawyer with criminal trial experience – to represent Abel. Donovan believes in the American justice system, so he provides his client with a zealous defense, even moving forward with an appeal when Abel is convicted on all counts. He does this to the chagrin of his colleagues at the firm, the judge in the case, and even his own family.

It would be one thing if the writers stuck to the maxim of “show, don’t tell” to illustrate the moral superiority of treating even the worst criminals with the same dignity and humanity granted all U.S. citizens. After all, the case can be made that it’s a lesson worth re-learning since the war on terror began – especially for those in positions of power. But Charman, Spielberg and the Coens don’t just show. They tell, and tell, and tell. Tom Hanks is one of the finest actors of his generation, and his performance in Bridge of Spies is as good as you would expect. But by the fifth or sixth time he explains the importance of due process to those who want blood, the point becomes excruciatingly belabored.

This heavy-handed dialog is coupled with some ham-fisted editing choices by long time Spielberg collaborator Michael Kahn. The editor makes some cutting decisions that bludgeon the viewer with their meaning. As the bailiff instructs all in the courtroom to rise, the film cuts directly to a classroom full of children with hands over hearts, reciting the pledge of allegiance. There is also a sequence – involving those same school children watching the infamous “duck-and-cover” educational film – that cuts between A-bomb imagery and close-ups of the children’s terrified faces, some of whom are weeping.

Thomas Newman’s score is particularly overwrought in places, especially in a scene that feels like it was shot specifically for inclusion in the trailer. Donovan is visiting with his client after the guilty verdict is delivered and he resolutely describes their next move to avoid the death penalty. The spy tells his lawyer a story about a man from his childhood who the secret police beat savagely. Each time the police knocked this man down, he would get back up. The music builds (melo)dramatically as Abel says Donovan is like the one his town called “the standing man.” You can probably guess that this term comes back into play in the final minutes of the film.

What should have been the real focus of Bridge of Spies – an exchange of U.S. and Soviet espionage agents – only comes in the back half of the film. But this is where Spielberg gets to show off his talents staging taut political intrigue and action sequences, two of his specialties. We’re shown the preparation for the CIA’s secret U-2 spy plane mission, which, in 1960, culminated in U.S. pilot Francis Gary Powers being shot down over Soviet airspace and taken prisoner. The breathtaking 360 degree camera pan around Powers’ plane, as he frantically tries to eject before nose-diving into oblivion, is masterful.

Now that the Soviets have “one of our guys,” and the U.S. has Rudolf Abel, clandestine plans for an exchange are set in motion. Since the two governments are locked in a cold war, they can’t deal with each other in an official capacity. The CIA asks Donovan if he will act as a civilian negotiator to trade Abel for Powers. Donovan agrees, and he travels to Berlin to begin work. At the same time, the Soviets are constructing the Berlin Wall. An American graduate student gets caught on the wrong side of the wall, and is arrested on trumped up espionage charges. Donovan learns of this and decides to do anything he can to free both Americans, against the express wishes of the CIA. All they care about is getting their soldier back before he can divulge too many state secrets.

The dramatic focus on Donovan’s tireless and often times dangerous attempts to free both Americans is where Bridge of Spies soars. Spielberg handles the cloak-and-dagger elements to the story just as expertly as he did in his 2005 thriller Munich. The director captures the fear and confusion felt by the citizens of Berlin as their city is ripped in half in a way that conveys the insanity of it all. The director achieves, in this portion of Bridge of Spies, exactly what he fails to do earlier in the movie. Instead of grand speeches about how freeing both Americans should be the priority, we see that this is the case through Donovan’s actions. His dogged efforts to do the right thing show (instead of tell) the lessons that the filmmakers want to teach.

Bridge of Spies is a film that could have greatly benefited from honing the tale Spielberg wanted to tell. Due to its flaws, it’s not the best version of the fascinating true story that could have been made, but it is a worthwhile effort for a story that more people should know.

Why it got 3 stars:

- Parts of Bridge of Spies are really effective, but the sections that aren't devolve into preachy didacticism. While I agree with the lessons being taught, there are much more dramatically satisfying ways to teach them, and Spielberg knows how to do that.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- Amy Ryan is a phenomenally talented actress. She's had roles in the past that prove it (see NBC's The Office, or HBO's The Wire). She needs better roles than what she's given here as James Donovan's wife. She has nothing to do in Bridge of Spies.

- Alan Alda doesn't get much to do either as Donovan's boss, but I wanted to take the opportunity to acknowledge him. He is basically the best.

- The late 50s/early 60s Berlin landscape Spielberg and his set designers/decorators recreate is wonderful. The scene where Donovan witnesses what happens to those Berliners trying to escape over the wall from East to West is particularly effective.