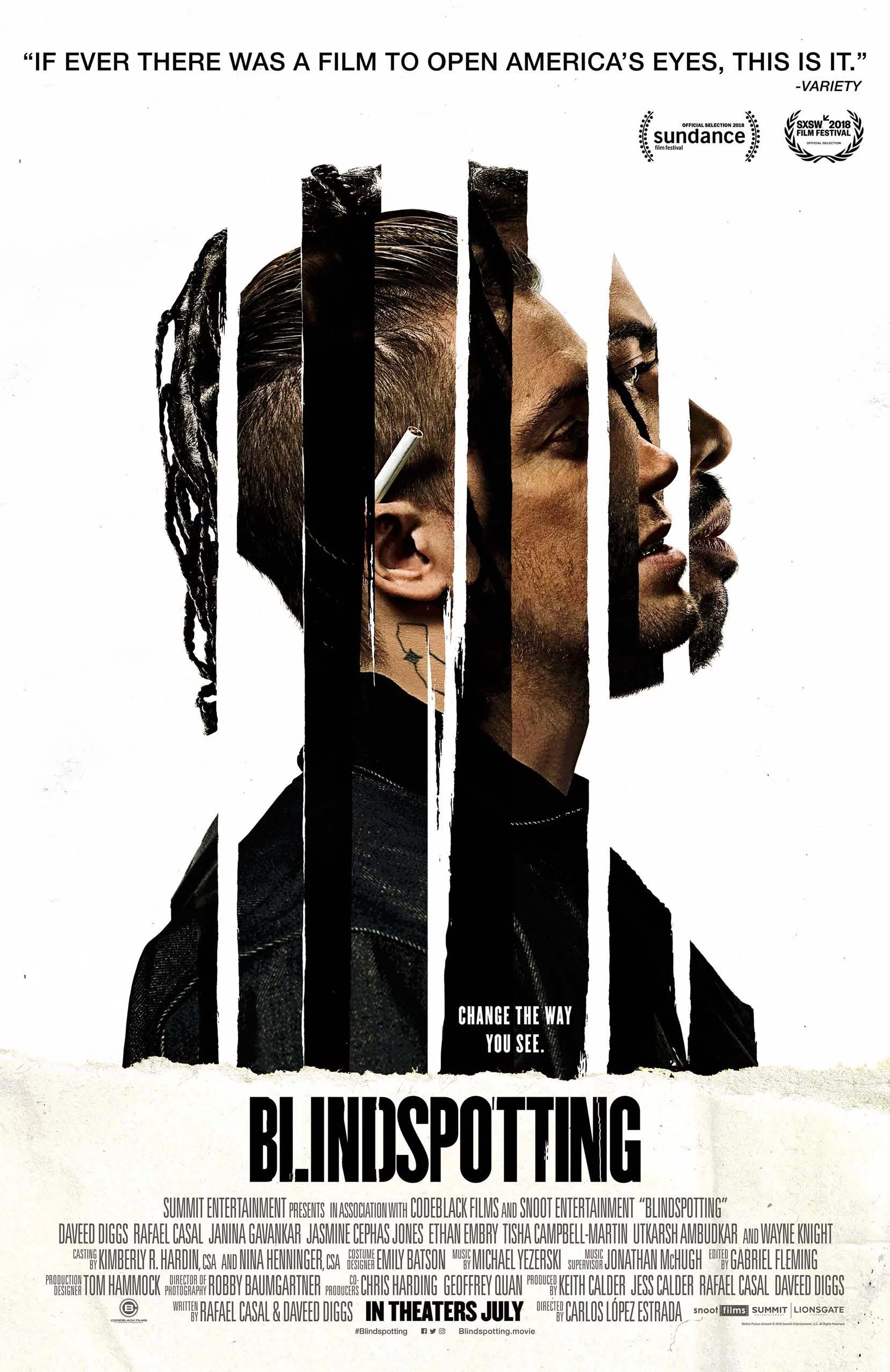

Blindspotting (2018)

dir. Carlos López Estrada

Rated: R

image: ©2018 Lionsgate

The themes and social commentary of Blindspotting are both timely and important, but the movie’s overall effect is one of slightness. That slightness is mostly a function of the way co-screenwriters and stars Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal chose to mix comedy and drama in their examination of gentrification, race relations, and toxic friendships. The result is uneven and too episodic, with comedic interludes that don’t quite fit alongside harrowing depictions of everything from lethal police misconduct to a young child getting his hands on a loaded gun. These moments, though, and many more like them, are incredibly powerful, and Diggs and Casal’s screenplay handle them with care and a great deal of emotional intelligence.

Blindspotting tells the story of childhood friends Collin (Diggs) and Miles (Casal) and takes place during the final three days of Collin’s probation following a conviction for assault. Even though Collin is the felon, it’s clear that Miles is the more explosive of the two. While Collin is trying to be on his best behavior to get through probation, so he can put his past behind him, Miles revels in being a bad boy. He buys an unregistered gun, and he’s always looking for trouble.

The two men work for a moving company in their hometown of Oakland. Collin’s ex-girlfriend, Val, who dumped him following the incident that got him arrested, did them a favor by getting them the job, and Collin is determined to win her back. Everything changes for Collin one night as he sits in the moving truck at a red light on a quiet street. He’s trying to make it to his probation-mandated halfway house before the 11 p.m. curfew. As he impatiently waits for the light to turn green, he witnesses events that have become familiar to anyone who pays attention to the news. A black man sprints past Collin’s truck. A cop is pursing him on foot. The officer yells for the man to stop. When he doesn’t, the cop draws his weapon, and as the man pleads “don’t shoot,” the cop fires four rounds into the man’s back.

Director Carlos López Estrada stages this pivotal moment in the film with a bold stylistic flourish. He uses one unbroken take and an inventive setup to show us all of the action simultaneously. The camera rests next to Collin, who looks out of the driver-side window of his truck. The cop stops next to the window as he draws his weapon. We see, in the truck’s large side-view mirror, the man who is fleeing from the officer. The cop fires his weapon. In the mirror, we see the bullets strike the man, and we see him fall to the ground. This sequence sets an expectation early in the film that Blindspotting will be unflinching.

For the most part, it is. Diggs and Casal are real-life childhood friends, and they spent the better part of a decade crafting the screenplay for Blindspotting. The two men grew up together in the San Francisco Bay Area. They wanted to address what they thought was missing from screen depictions of their native area as well as the massive changes it was going through due to aggressive gentrification.

Gentrification is the practice of wealthy developers or citizens (who are usually white) coming in to an economically depressed section of a metropolitan area and pumping money and resources into it. As a consequence, this forces out the original residents (who are usually people of color) because they can no longer afford the now higher-priced goods, services, and property taxes that gentrification brings.

Blindspotting shines a light on this process in hilarious and cutting ways. The bits of comedic relief that work best come from these observations. The opening montage of the movie is a clever series of split-screens that juxtapose the two worlds – the culturally diverse residents who have lived in these neighborhoods for decades and the newer, whiter usurpers – that are colliding. Throughout the picture, Miles is incensed that his beloved Kwik Way burger-joint has changed their menu to cater to the new yuppie hipster invaders. The fries are transformed into “potato wedges,” and Kwik Way now caters. It’s blasphemy, as far as Miles is concerned. Kwik Way shouldn’t cater, because it’s quick, and you get it on the way home, hence the name.

Collin is a little more open to changing with the times, like when he buys a ten-dollar (“TEN DOLLARS,” screams Miles) bottle of green health juice (which looks like pureed baby food) from the local corner store. Collin is only attempting to get back in the good graces of Val – who practices things like yoga and mindfulness meditation, to the consternation of Miles – and the movie judges him for it. At one point, there is an overhead shot of the store counter, and all we see is the bottle of green juice and Collin’s hand as he places two fives on the counter. It’s a visual representation of selling out, but we can’t be too hard on Collin. He’s just doing the best he can under circumstances over which he has very little control.

That lack of control is put into stark relief throughout Blindspotting. The movie draws attention to how trapped Collin is due to his brand-new felon label. He feels he can’t speak out about witnessing an officer of the law shoot a fleeing man in the back. He knows that as a convict, who was late for curfew anyway, he will be crushed under the weight of the system if he tries to do the right thing. So, he keeps his mouth shut.

The supervisor of his halfway house informs Collin that he is expected to be perfect. He’s a convicted felon, the man tells Collin, and he will always be so until proven otherwise. “Prove otherwise at all times,” he says, giving us a hint of how unattainable Collin’s expected behavior is, because who among us is perfect?

The movie also delves into the issue of toxic masculinity. Miles is constantly hustling to make extra money by selling things like used curling irons at a beauty salon or unloading a salvaged sailboat (these are two of the comedic episodes that don’t quite work). When he isn’t selling, he’s wrapped up in projecting his tough guy persona. In a stylized flashback late in the movie, we learn about Miles’ own part in the assault that got Collin put behind bars. Speaking personally, as someone who deals with my own anger issues, there is a great amount of emotional weight behind Val’s reaction to the incident. We are all responsible for how we let our emotions affect us, and men need to realize how others see our emotion-fueled actions.

Anger, rage, and injustice all build to an explosive climax in Blindspotting that, while powerful, borrows a little too heavily from the hip-hop style of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s stage musical Hamilton. Daveed Diggs originated the roles of Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson for the show on Broadway.

Throughout the film, Collin and Miles work on rap lyrics that incorporate elements of their everyday lives. These practiced lyrics come spilling out of Collin at a pivotal moment. Diggs’ performance and Estrada’s direction make the moment compelling, but like the misplaced bits of comedy, it doesn’t quite fit within the world that movie has created. This sequence, like the rest of Blindspotting, carries a vital message, and its impact is only slightly dampened by a few of the filmmakers’ stylistic choices.

Why it got 3.5 stars:

- The parts of Blindspotting that work are phenomenal. The parts that don't work just sort of sputter along until the plot gets going again. As a film that taps into the current zeitgeist of race relations and police brutality, it's a must see.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- Everything that takes aim at gentrification and stuff that white people like in general is priceless. There was a blog titled "Stuff White People Like" that is also good for a laugh. It hasn't been updated since 2010, but all the old posts are still available. A few of my favorite of these moments from the movie: Val attends Soul Cycle classes, and Collin and Miles see a white dude with a huge beard riding a novelty bike down the street.

- At one point Collin and Miles are helping an artist (played by the great Wayne Knight) move. The artist asks them to have a moment of truth with each other by staring into each other's eyes. They do, and the movie creates an earnest dramatic moment out of it, but it then proceeds to break that moment of tension with a bit of comedy. It's an unsatisfying resolution to the scene.

- There is one unbelievably powerful sequence involving Collin as he goes on his morning run. He passes through a cemetery, and the ghost of the man who was shot by the police officer, as well as other people buried in the cemetery, haunt him. The scene has a huge impact and is staged very effectively.

Close encounters with people who don't know how to act in a movie theater:

- For this screening, Rach and I attended a theater that just opened in Dallas. It's part of a chain called Cinépolis. The hilarity of attending a screening of Blindspotting at this theater is that it's big selling point is being a luxury theater with fully reclining seats and gourmet food served to your seat while you watch the movie. It's also located in a heavily gentrified part of town. Of course, there were a pair of very well-to-do white people right next to us who were so concerned with their food orders and food service that it was a wonder they even knew they were there to watch a movie at all. It was obnoxious, but in a way, I really enjoyed the irony of it all.

Up Next at The Forgetful Film Critic:

- Last year's Get Out began a renaissance of people of color putting their own experiences with racism in America on film. This year has already seen Sorry to Bother You and Blindspotting. Later in the year we'll get Monsters and Men and The Hate U Give. Next week, I'll take a look at one of the masters of addressing race on film. Spike Lee has made a new movie that tells the true story of a black man in the 1970s infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan. It's called BlacKkKlansman, and it is sure to be anything but boring.