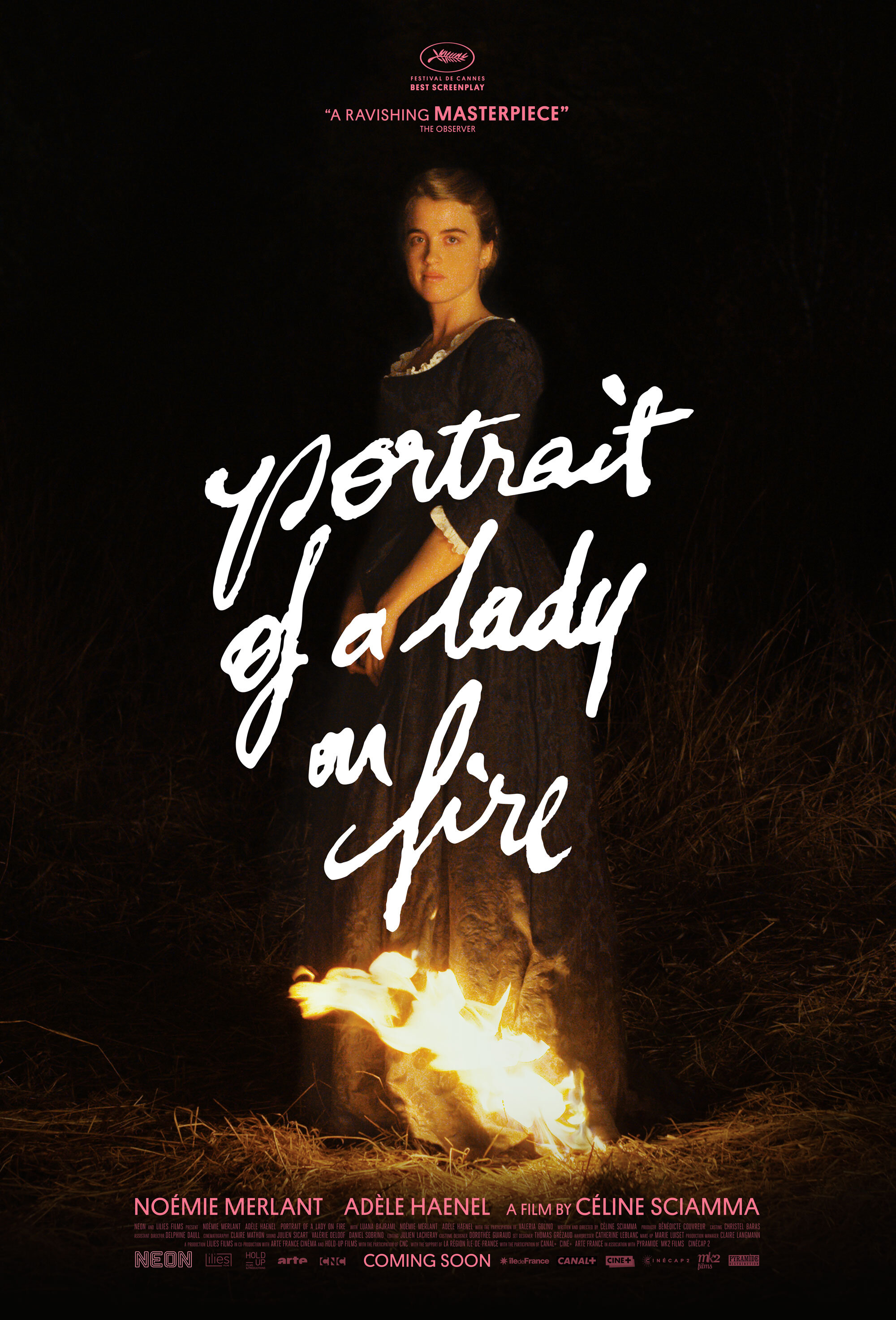

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

dir. Céline Sciamma

Rated: R

image: ©2019 Neon

It would be hard to overstate the rapturous reaction I had to Portrait of a Lady on Fire. There is an overwhelming beauty to every aspect of the picture. From the cinematography, shot composition, and acting, to the delicate lyricism with which writer/director Céline Sciamma tells her story, this is an exquisite work of art.

Set in late eighteenth-century France, Portrait of a Lady on Fire details a passionate love affair between two women, Marianne and Héloïse. Marianne is an artist, and a wealthy countess has hired her to paint a portrait of her daughter, Héloïse. The countess is eager to marry off her daughter to a nobleman in Milan. Because of the great distance and treacherous travel conditions, the portrait of Héloïse will be sent to the nobleman to entice him to agree to marry her.

Only, Héloïse has no desire to be married. She has already foiled the attempts of another painter to create a portrait by refusing to sit long enough for him to capture her likeness on the canvas. So, the countess hatches a plan to introduce Marianne to her daughter as a walking companion. Marianne will observe Héloïse on their walks and paint in secret.

The love affair between the two women, which blossoms in slow motion over the course of a week when the countess leaves town on business, is breathtaking in Sciamma’s hands. Her movie is gloriously free of any aspect of the male gaze, which lends it a fresh, exciting perspective. It also has the feel of very authentic and personal filmmaking. Sciamma is herself an out lesbian, who amicably ended a romantic relationship with Adèle Haenel – the actress who plays Héloïse – not long before they began work on Portrait.

Aside from the LGBTQ concerns of the film – Sciamma uses the distant past as the setting for her story, even though in many parts of the world today, women (and men) in love are forced to be as secretive as in the 1700s – Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a bold, unapologetically feminist film. There is a subplot in which Héloïse and Marianne help the former’s maid, Sophie, get an abortion. There is zero moralizing about this. The process is treated as a fact of life, which, to the perpetual outrage of Christians everywhere, it is.

The artistry goes hand-in-hand with the message as the three characters attend a feast held by a group of women after dark on a beach. The sublime magic-hour shot of the characters walking to the party, the sunset creating majestic purple clouds as their backdrop, is one of the greatest cinematic images of 2019. Moments later, all the women at the feast begin singing an a cappella chant, which swept me away in its ethereal beauty.

Héloïse’s situation is also a commentary on the patriarchy, an institution which, while not as all-powerful as 200+ years ago, still exerts an unacceptable amount of control over women’s lives. Héloïse’s mother has ripped her away from her life in a convent after Héloïse’s sister, it is heavily implied, committed suicide because of her own impending arranged marriage. With no one else to secure the family’s position, the countess must offer up her only surviving child to any man who will have her.

A discussion between Marianne and Héloïse about the situation yields one of the most insightful quotes of the film. When Marianne asks Héloïse about the strict lifestyle in the convent, and if she was glad to escape it, Héloïse surprises Marianne by describing the dynamic of the nuns: “Equality is a pleasant feeling,” she says.

Aside from its passionate love story and progressive political stance, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is also about beauty, art, and those transcendent moments when the latter is able to perfectly capture the former.

The artistic choices that make up the film itself speak to this theme. Sciamma frames most of her movie as a series of close-ups. It makes sense, because the emotional heart of the movie is Marianne trying to capture and translate the truth of her subject’s face onto a canvas. Sciamma delights in the playfulness of her camera during one sequence when Marianne takes furtive glances at Héloïse as they walk along the isolated Brittany island beach of the film’s setting. The camera views the two women in profile. Their faces take turns obscuring each other as Marianne steals a look then quickly turns her head when Héloïse glances over at her new companion.

Cinematographer Claire Mathon – who won praise in 2019 for her work here and on the French film Atlantics – paints with light. Her photography is sumptuous and gorgeous. Mathon takes care to brightly light each of Sciamma’s close-ups of Marianne and Héloïse; they are endlessly fascinating to look at.

Much of that has to do with the actors Sciamma cast in her love story. Both Haenel and Noémie Merlant, who plays Marianne, have striking features. Haenel, in particular, has an indecipherable Sphinx-like quality, especially in the early scenes when we are trying to figure out her true feelings for Marianne. Her smile is as enigmatic and beguiling as the Mona Lisa’s.

It’s fitting, then, that Haenel’s visage is the last thing we see. In this celebration of love, beauty, and art, music takes a pivotal role in the final minutes of Portrait of a Lady on Fire. In a call back to a discussion the two lovers have about the power of music, our last vision of the film, and of Héloïse, is her face transported into rapture by both a particular piece of music and the flood of memories that it invokes. It’s a poignant, exultant, and bittersweet ending to a moving and emotionally rich film.

Why it got 4.5 stars:

- Portrait of a Lady on Fire is one of the most emotionally rich, artistically satisfying movies of 2019. This is now the big one that I really regret not having seen before putting together my top ten of the year.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- I was hooked into this movie from the opening framing device, when Marianne is teaching painting to a class full of women. One of her students pulls out the eponymous painting and asks for the story behind it.

- The dialog is gloriously sparse and well-written (at least the English subtitle translation is). It’s master-level exposition. We learn everything we need to know at the start of the film about Héloïse’s situation in a few sentences.

- The way Sciamma’s camera follows Héloïse as the two women go for their first walk is mesmerizing.

- The film makes sure to emphasize the time, care, and craft it takes to produce a beautiful portrait. I think that Sciamma here is commenting on all quality works of art.

- The sound design in Portrait is just as crucial as the visuals. The sound of twigs popping in fires is especially potent.

- I wrote a lot about close-ups in the review. There is one that I think is particularly brilliant. Sciamma uses a disorientingly close shot so that I confused an armpit with… another bit of the female anatomy (hint, French women don’t shave under their arms).

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- I saw this at the tail end of it’s run at my local Alamo Drafthouse during a two-week engagement. There was exactly one other person in the theater with me. I’m sure there will come a day when I have the whole theater to myself, but not yet!