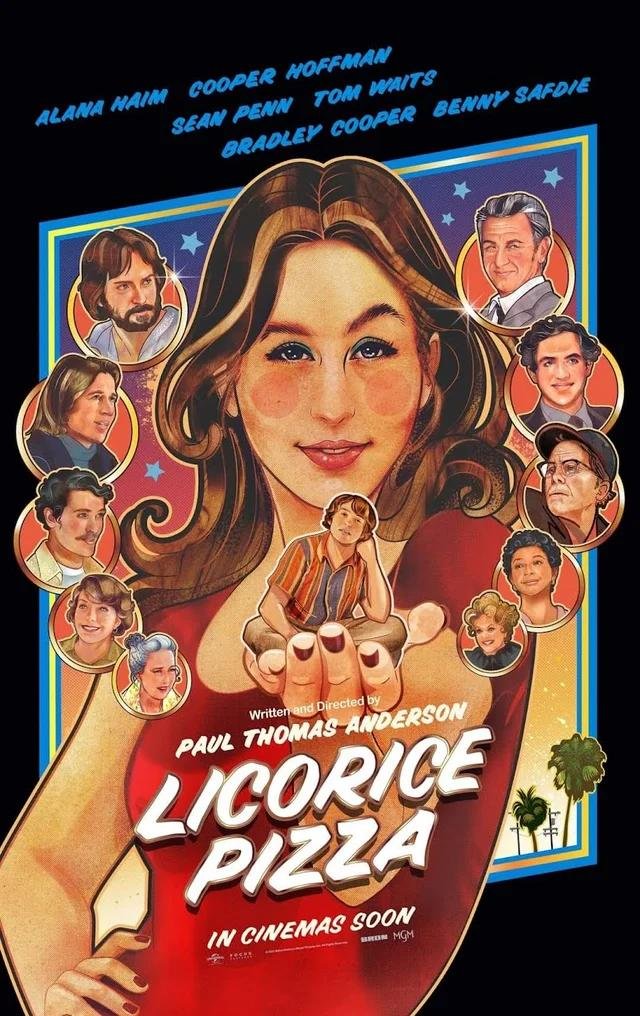

Licorice Pizza (2021)

dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

Rated: R

image: ©2021 United Artists Releasing

Though very different in story and theme, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza is destined to play on a double bill in repertory theaters and stoners’ home theaters alongside Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Both films are fantastic examples of the hangout movie: light on plot, heavy on atmosphere, these are movies that are more about an aimless, meandering pace and watching the characters simply be and not necessarily do. Tarantino himself coined the term to describe perhaps the first ever hangout movie, Rio Bravo.

Other examples include Fast Times at Ridgemont High and American Graffiti – Anderson has credited both as major inspirations for Licorice Pizza – as well as Anderson’s own Boogie Nights and Magnolia.

Another contender for that imagined double bill with PTA’s latest would be one of the greatest hangout movies ever made: Dazed and Confused. That movie, alongside Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Licorice Pizza, deftly recreates a late ‘60s/early ‘70s vibe that is infectious. I thought of the Hollywood/Licorice Pizza connection first because of their proximity in setting – L.A. and the San Fernando Valley, respectively – and both movies’ exploration of the entertainment industry of the time.

Licorice Pizza follows the nascent romance between 15-year-old Gary Valentine and 25-year-old Alana Kane. Gary is struck, as if by lightning, upon seeing Alana for the first time. She’s working as a photographer’s assistant, taking yearbook photos at Gary’s school.

If there’s reason to condemn Licorice Pizza, it’s because of Gary and Alana’s age difference. It was less than a month ago that I eviscerated Red Rocket for its version of just such a May-December “romance.” As is the case with everything in life, though, context is key. The circumstances surrounding the characters in both movies must be taken into consideration.

The 40-something protagonist in Red Rocket is a predator, plain and simple. He wants nothing but sex from his target, both for himself and as a way to make money using her body. The on-again, off-again tempestuousness between Gary and Alana is about two confused young people struggling with their emotions for one another in an honest, heartfelt way.

There is no outsized power disparity between Gary and Alana. It’s Gary’s confidence (which often manifests as cockiness) that draws Alana to him. Ten years is a sizeable age disparity, but between these particular characters, it feels smaller. Alana is somewhat rudderless in her life; that fact plays into why she’s drawn to Gary, who always has a plan, even when it’s a not terribly well thought out one.

Another important factor to consider is that Gary and Alana never consummate their relationship. It is a romance in the purest sense. The closest the pair come to physically acting on their feelings is when Alana bares her breasts for Gary, at his request. One of the biggest laugh lines of the movie comes when Gary then asks to touch them, at which point Alana slaps him in the face for his audacity.

One other moment of sexual tension between Gary and Alana comes in a bravura moment staged as the two are lying on a waterbed. Anderson shoots the pair from above as they lie together, with a backlight coming up through the water in the mattress. It’s an ethereal moment that underscores Gary’s hesitation as he reaches out to caress Alana’s body – as you might expect from any 15-year-old boy, his focus, once again, is on Alana’s breasts – before chickening out and settling for holding her hand instead.

This is a love story more akin to the chaste one in Harold and Maude – sadly, I can’t ponder the connection more deeply, as I’ve yet to catch up with that Hal Ashby film – or the admittedly much more graphic one in Call Me by Your Name.

Gary is based on film producer and former child actor Gary Goetzman, the cofounder, with Tom Hanks, of the production company Playtone. Paul Thomas Anderson and Goetzman are friends, and Anderson was inspired by Goetzman’s tales of Hollywood in the ‘70s and his own entrepreneurial ventures – Goetzman sold waterbeds at one point, as Gary does in the movie.

As Tarantino did for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Anderson creates a fictional world that blends and crosses paths with elements and people in the real world. We see Gary on stage in a variety show with Lucy Doolittle, a character loosely based on Lucille Ball. (Goetzman starred as one of the children in the 1968 Ball/Henry Fonda vehicle Yours, Mine and Ours.)

Gary – as his real-life counterpart did – installs a waterbed in the house of (in)famous movie producer Jon Peters. Bradley Cooper devours the scenery in his hilarious send-up as Peters. Anderson decided to make his fictionalized version of the producer a stand in for every monstrous Hollywood producer of the time period once he got the real Peters to sign-off on the project.

(Don’t feel too bad for how Peters comes off in Licorice Pizza; his sole stipulation for PTA using his name in the film was that Anderson include his favorite pick-up line. If you’re interested in knowing more about Peters, I highly recommend checking out the gossipy book about him by Nancy Griffin and Kim Masters – Hit and Run: How Jon Peters and Peter Guber took Sony for a ride in Hollywood. It’s a jaw-dropping and hilarious read.)

Sean Penn puts his stamp on Jack Holden, a character loosely based on Hollywood Golden Age icon William Holden. With Gary’s help, Alana decides to give acting a try, which leads to a delightfully diverting sequence in which she goes to dinner with Jack. The inimitable Tom Waits turns up in the sequence as director Rex Blau – think an old and crusty John Ford – who convinces Jack (without much effort) to stage a reenactment of one of Jack’s most famous movie stunts. Gary literally runs to Alana’s rescue when her part in the reenactment goes sideways.

The act of two characters running towards each other – probably the most powerful representation of romance in cinema that doesn’t involve physical contact, at least until the last second – is a motif that Anderson goes back to again and again throughout Licorice Pizza. It allows the director to stage his signature tracking shots, of which there are many here.

As he did with his breakout hit Boogie Nights, Anderson proves himself to be an expert at recreating the look, sound, and feel of 1970s L.A.

Anderson and his co-cinematographer, Michael Bauman, shot Licorice Pizza on 35mm with lenses used by famed cinematographer Gordon Willis – who shot all three Godfather pictures – that date back to the time period of the movie. Their efforts give the movie an authenticity that’s hard to overstate. Production Designer Florencia Martin and Costume Designer Mark Bridges add to that authenticity with their meticulous craftsmanship.

The soundtrack for Licorice Pizza is filled with hits of the era. One of the most standout sequences of the film uses Bowie’s Life On Mars? brilliantly. The wall-to-wall musical landscape further builds an undeniable sense of time and place within the movie.

Adding to the loose, almost improvisational style of Anderson’s film is his casting of Cooper Hoffman in the role of Gary. Hoffman is the son of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, who was a frequent collaborator with Anderson. He appeared in five of the seven films Anderson directed before Hoffman’s tragic 2014 accidental drug-overdose death.

This is Cooper Hoffman’s first acting role and the 18-year-old shows an incredible naturalism as Gary. Hoffman’s lack of experience as an actor gives his character a real authenticity that matches perfectly with his costar, Alana Haim, who plays Alana Kane.

Haim and her two older sisters make up the rock band Haim, and Paul Thomas Anderson has directed several of the band’s music videos.

Donna, the Haim sisters’ mother, was even one of Anderson’s teachers when he was a boy. Both she and the Haim sisters’ father also appear in the film, as does Anderson’s wife, the hilarious comedic actress Maya Rudolph. Anderson and Rudolph’s children also make cameo appearances. This friends-and-family approach to Licorice Pizza adds to the movie’s effective hangout vibe.

While I have ultimately chosen to defend the (sizeable) age-gap romance at the heart of the movie for reasons I’ve detailed – and for a decidedly more personal reason which I won’t, IYKYK – I understand anyone who feels queasy about it. Anderson is seemingly trying to slide by with the “that’s the way it was back then” defense by setting the movie within the time period that he does.

That also serves as his reason for the inexplicable inclusion of a character that uses a horrifically stereotypical Japanese accent to speak to his Japanese wife. (Actually, he does it to two different women. We see the character in two scenes, and in the latter one, he has divorced his first wife and is remarried to another Japanese woman.)

The character is Jerry Frick, a real-life restauranteur who opened the first Japanese restaurant in the San Fernando Valley called The Mikado. In the movie, Gary is friends with Frick. Anderson has made statements about how he is merely accurately representing the racism of the time period. He’s commented about how even today, his mother-in-law, who is Japanese, encounters white Americans who speak to her using an outlandish Japanese accent.

Anderson doesn’t take care, however, to code these moments as anything but laugh lines. That is made apparent in a tweet by film critic David Chen about his own experience watching Licorice Pizza with a mostly white audience, who laughed at the disgusting caricature.

Wherever you come down on the more troubling elements of Licorice Pizza, it’s undeniable that Paul Thomas Anderson has made a rich, dense, complex piece of art here. For the most part, I enjoyed hanging out with these characters and being blissfully carried away to the early 1970s San Fernando Valley. Despite its missteps, Licorice Pizza is a movie I can see myself returning to again and again to visit a place in time that was gone before I could experience it firsthand.

Why it got 4 stars:

- My love for Licorice Pizza all comes down to tone and mood. The former is beautiful and the movie has the latter for days.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- One of my favorite bits (which I didn’t even get to in my review) is the brief relationship between Alana and one of Gary’s acting contemporaries, Lance. The budding romance goes off the rails when he tells Alana’s deeply devout Jewish parents that he’s an atheist, and that’s why he won’t say a prayer before they all eat dinner together. I stan Lance’s honesty and no-bullshit attitude so much. He’s played by the hilarious Skyler Gisondo, who seems to be popping up in everything I’m watching lately.

- “You’re a thinker! You think things!” Funniest insult ever?

- There’s an amazing blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo by PTA regular John C. Reilly as Fred Gwynne.

- There’s one line in the movie that I’m convinced is a reference to a line in Goodfellas: “Have fun in Attica, dickhead.” Anybody out there who agrees with me?

- If you read my review for Spencer that I wrote a few weeks ago, you know how I feel about Jonny Greenwood. His score for Licorice Pizza is good, but it takes a back seat to the transcendent rock soundtrack.

- The way that Gary looks at Alana. Everyone should have someone they look at like that. Luckily, I do.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- I saw this at the Cedars Alamo Drafthouse. Rae went with me. She was not amused. Thank Osiris that I didn’t hear a single laugh from the 10 or so people in the crowd during those Japanese accent scenes.